The Price of Wealth: Scarcity and Abundance in an Unequal World

Date

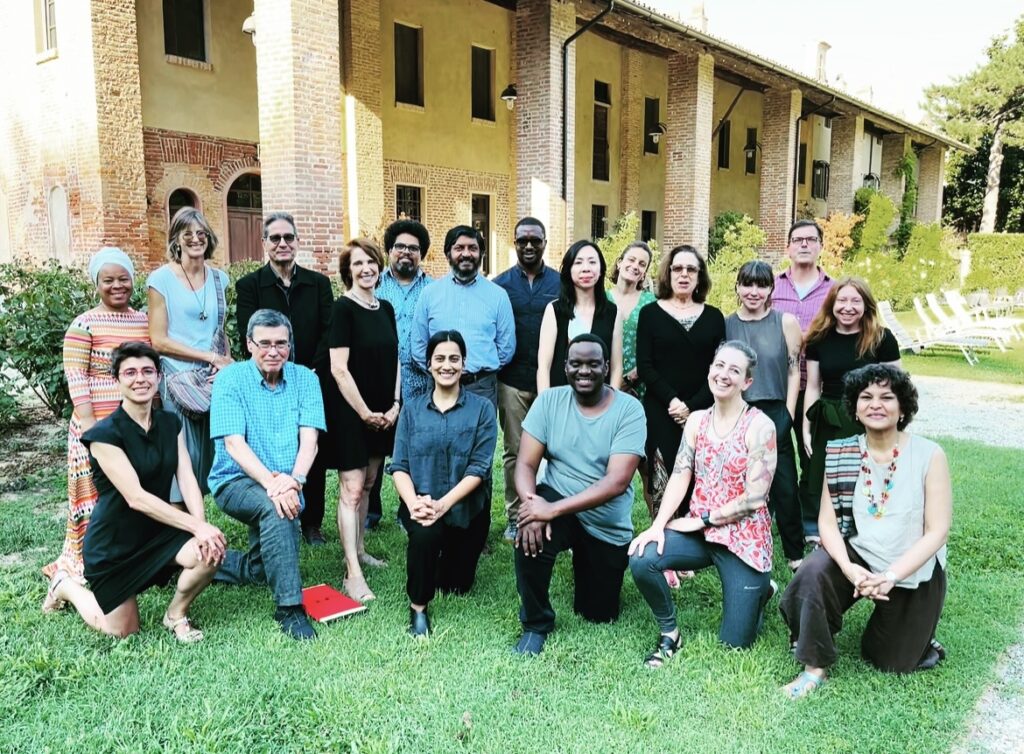

Aug 5-11, 2022Organized by

Teresa Ghilarducci , Rick McGahey and Gustav PeeblesLocation

Mezzana Bigli, Pavia, ItalyParticipants

- Donna Auston Wenner-Gren Foundation, USA

- Nelson Barbosa Escola de Economia de São Paulo, Brazil

- Amita Baviskar Ashoka University, India

- Grieve Chelwa The New School, USA

- Kimberly Chong University College London, UK

- Julia Elyachar Princeton University, USA

- Teresa Ghilarducci The New School, USA

- Jayati Ghosh University of Massachusetts Amherst, USA

- Isabelle Guérin CESSMA, France

- Darrick Hamilton The New School, USA

- Ingrid Kvangraven King’s College London, UK

- Rick McGahey The New School, USA

- Suresh Naidu Columbia University, USA

- Gustav Peebles The New School, USA

- Michael Ralph Howard University, USA

- Vimal Ranchhod University of Cape Town, South Africa

- Gustavo Lins Ribeiro Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, Unidad Lerma, Mexico

- Danilyn Rutherford Wenner-Gren Foundation, USA

- Caroline E. Schuster Australian National University, Australia

- Erin Simmons The New School, USA

- Nishita Trisal Harvard Academy for International and Area Studies

ORGANIZER’S STATEMENT: The world is awash in wealth. We frequently hear of the growing number of billionaires and are consistently confronted with flashy new infrastructure bedecking the planet in the form of airports and high-speed trains. At the same time, globally resurgent nationalist and anti-democratic forces have often gathered their strength from the disgruntlement experienced by the many who feel “left behind” or pushed back, as wealth surges forward and inequality grows to historic levels.

Both anthropologists and economists have been grappling with the fact that the price of wealth is indigence and inequality. We propose to bring these two disciplines into dialogue around this important issue, in order both to shed light on the problems themselves, and to increase methodological and theoretical understanding and hopefully foster future cooperation.

Adam Smith transparently connected wealth and poverty, when he wrote that “the affluence of the few supposes the indigence of the many.” In a much cited article, Marshall Sahlins rewrote Smith’s dictum for an anthropological audience, asserting that “Poverty is not a certain small amount of goods, nor is it just a relation between means and ends; above all it is a relation between people. Poverty is a social status.” From many different angles, our symposium will address the structural relationship between wealth and poverty, noting not only its reliance on hierarchical questions of social status, but also on the role of economic production itself. By interrogating the price of wealth, we hope to shed new light on emergent challenges confronting both individuals and communities.

This five-day seminar will feature a series of papers and responses, along with open conversation, designed to simultaneously investigate the price of wealth, while also transcending a disciplinary divide that has unnecessarily bifurcated discussion about the price of wealth into various disciplinary camps. Participants from Anthropology and Economics will author papers on specific issues and engage with one another’s scholarship openly and rigorously through conversation, reflection, and commentary.

Alas, for too many decades, Anthropology and Economics have gone their separate ways, each discipline more or less talking past the other. For anthropologists, this occurred at the time of the so-called “Formalist-Substantivist Debate” of the 1950s and 60s, when “economic anthropologists” left the American Anthropological Association and created their own Society for Economic Anthropology. This debate hung on Karl Polanyi (whose book The Great Transformation has had a major influence among economists) and his many followers’ insistence that economic theory could only be applied in “market societies,” and not in “non-market” or “primitive” ones.

From the Substantivist perspective, “price” itself is only something that is conjured forth after a vast campaign to “disembed” the economy from social life. After the Formalists decamped, the Substantivists became the dominant voice within broader anthropological circles, gradually instilling a general disavowal of economists’ alleged commitment to “homo economicus.” Over a similar time period, many Economics papers began featuring formal mathematical models of individual maximizing which are said to provide the hypotheses “tested” by quantitative methodology, but much of the empirical work does not in fact depend on such formalization. As such, many empirical economists’ research today is, in practice, much less committed to “proving” the existence of the utility-maximizing “homo economicus.”

Although these are important background issues, our symposium will not delve into this older theoretical debate. Instead, we will continually grapple with the methodological divide that emerged out of it, in which anthropologists became committed to qualitative data, while economists built much of their empirical edifice out of quantitative data. In the ensuing years, the empirical methodological divide has even acquired a hierarchical hue, with each camp claiming to have a firmer portrait of “the truth” and thus, the solid uses to which such truths could be put. In some ways, the divide between Anthropology and Economics reflects a larger—and far older— trend within universities themselves, wherein the scientific-Baconian demand to only tally up “sense-perceivable” natural phenomena has pushed against the theological tradition of studying the “ineffable.” As this gulf deepened, unhelpful misunderstandings blossomed, where each discipline almost blithely dismisses or simply ignores the findings of the other.

Symposium #161