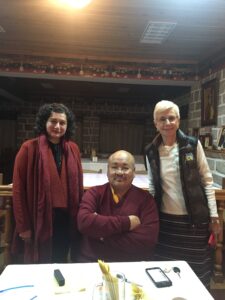

Interview: Ritu Verma and Francoise Pommaret

In 2017 CLCS, Royal University Of Bhutan received a Wenner-Gren Institutional Development Grant to support the development of a doctoral program in anthropology. The implementation of this grant was overseen by Dr. Ritu Verma, the Institutional Development Grant International Coordinator, Adjunct Professor at The College Of Language And Culture Studies, (CLCS) and Dr. Francoise Pommaret, IDG Coordinator Bhutan, Adjunct Professor at CLCS / Director of research at the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique. France. Wenner-Gren had the opportunity to ask Drs. Verma and Pommaret about how they initially became interested in anthropology as well as the current state of anthropology in Bhutan and how the Institutional Development Grant will help the Royal University of Bhutan.

First can you tell us a bit about yourself and how you came to be interested in anthropology? Who have been the anthropologists that have most influential in your own personal formation and why?

Francoise: I was brought up in Central Africa and in contact with other people from a very young age so I understood there were different ways of thinking and living. This might have been my first unknowing contact with anthropology. At the university in France, I graduated first in Classical Greek and Latin. By then I started travelling in Asia and decided to take Asian studies, (history, history of art and archaeology at Paris La Sorbonne) as well as Classical Tibetan at INALCO, Paris. After my MA on vernacular architecture in Ladakh (India), it dawned on me that buildings could be understood only through the people living in it and from then I moved to a Ph.D. program in anthropology at EHESS (Ecole des Hautes études en Sciences Sociales) Paris. My dissertation was on women who come back from the netherland in the Tibetan world (‘das log) and it was published in 1987 by the CNRS ”Les revenants de l’au-delà dans le monde tibétain. Sources écrites et traditions vivantes.” The sub title showed my interest for interdisciplinary research and my strong commitment to history. In the 1980s I was called in French an ethno-historian. Therefore I do not have a purely anthropological background and my research methodology has always been based not so much on theory, but on written and oral sources as well as field research. The disdain of history among some anthropologists has always been a source of irritation for me but I was reinforced in my belief by my EHESS professors such as Bernot (Burma) and Condominas (Indonesia) and other French luminaries from the School of Annals such as Fernand Braudel, Leroi-Ladurie, Georges Duby and Burguière amongst others. Amongst the Anglo-Saxons scholars, besides the founding fathers such as Malinowski, Evan -Pritchard or even Boas, I am really inspired by Geertz as well as closer to my field by Ortner and Levine. I read and knew Levi-Strauss, some of his ”fulgurances” have been important to me, but the fact that structuralism does not consider the historical dimension as important has always been a problem, especially when working in a culture where history and written sources are so important. So my approach to anthropology is rather classical and not influenced by post-modernist theories.

Ritu: Although I didn’t begin my career as an anthropologist, the discipline captivated my imagination. I started my career as a civil engineer working on international infrastructure projects (PEng McGill University), but was deeply concerned about the social, cultural and environmental impacts on people, their communities and environment. My engineering degree didn’t provide the conceptual foundation to systematically analyze such projects, or the resistances to them. This interest drew me to pursue an MA in International Development at the Norman Paterson School of International Affairs at Carleton University. Making the transition from the biophysical to the social sciences was challenging, but I flourished intellectually. I was attracted to ethnography – spending extended periods of time with people who are most affected by development and scientific interventions not of their choosing – and anthropological debates about development. From this intellectual awakening, I carried out a Ph.D. in Anthropology at School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. Building on George Marcus’ idea of multi-sited ethnography, I engaged in what I termed a multi-ethnographic research, focusing on the disconnects between the socio-cultural and working worlds of development practitioners and Betsileo farmers in the Central Highlands of Madagascar, through fine-grained ethnographies of both domain of actors. The research illustrated how development critically shapes the lives of so many actors, but also creates deep dissonance and disconnects in knowledge, culture and experience, and this influenced my subsequent research with international development research institutions in East and Southern Africa and the Himalayas. With ethnographic insights and lived experience in the inner-workings (the conceptual and institutional apparatus), social life and culture that shapes the development machine and delimits its engagement of culture, my interest in development alternatives that value culture grew exponentially. Thus, anthropology has been a strong guiding force in my career, and led me to Bhutan and my present research which explores the conceptual and policy innovations, as well as ethnographic gaps, of Bhutan’s alternative development path of Gross National Happiness. Seminal works in the anthropology of development such as “Red Tape” and “Postcolonial Development” by Akhil Gupta, “the Anti-Politics Machine” by James Ferguson, “False Forest History” by James Fairhead”, “Negotiating Local Knowledge” by Johan Pottier, “Laboratory Life” by Bruno Latour and “Cultivating Development” by David Mosse inspired and influenced my own thinking about development. These anthropologists, as well as Villia Jefremovas, Joachim Voss, Fiona Mackenzie, Christopher Davis, Sherry Ortner and Nancy Levine provided invaluable intellectual guidance in my career.

Can you tell us a little about anthropology in Bhutan? What are the pressing questions and concerns for the discipline there?

Francoise: Anthropology in Bhutan is not only a new academic subject, it is a new concept. When I arrived in Bhutan in the early 1980s, this was a concept that did not exist and the closest to it was cultural studies, largely dominated by Buddhist studies (see Pommaret “Recent Bhutanese scholarship in History and Anthropology”, in Journal of Bhutan Studies: Special issue on the Bhutan panel of the European South Asian Modern Studies Conference Edinburgh University 2000, Centre for Bhutan studies, Thimphu, vol.3 n° 2, Winter 2000, 139 -163). The opening of Bhutan in the late 1990s and the influence of Bhutanese who studied abroad allowed the first field studies conducted by Bhutanese especially in the field of rituals. These, as well as the propagation of BBS ( Bhutanese TV) programs on different aspects of the culture and the GNH pillar on preservation of the Culture, created an awareness which led to the understanding of the concept of anthropology. Lastly the pride that the Bhutanese have in all aspects of their culture, played an important role in this awareness. The pressing questions are the establishment of an academic program in anthropology which besides Himalayan anthropology, will address contemporary and important topics for Bhutan: development, politics, gender issues and spiritual environment. The need of a course in research methodology in anthropology is paramount and should be included in the academic program. Lastly, Bhutan needs to train anthropology researchers and lecturers as only 5 Bhutanese have now a PhD in anthropology.

Ritu: Bhutan represents both a relatively unstudied anthropological and ethnographic terrain as well as a country where there is a dearth of anthropological analytical expertise required to support a nation that is facing numerous socio-cultural and development challenges as it negotiates globalized world. It is regarded as the least anthropologically studied belt in the Buddhist Himalayas. The opportunities for anthropologists to carry out research on Gross National Happiness – the country’s guiding philosophy for development that holds culture in equal weight with other domains of development (sustainable and equitable development, environmental conservation, good governance) – are significant. Over the past few decades, tertiary education has evolved and developed in promising ways (with formal national education system and universal education coming into force in the 1950s), albeit with acute under-representation of anthropology. At the beginning of this millennium, anthropology was still in its infancy in Bhutan. Today, Bhutan continues to lag behind in developing the academic discipline of anthropology. There are a handful of qualified anthropologists with Ph.D.s in the country, with new promising scholars about to join its ranks – all obtaining their degrees internationally. Although anthropological research on the impacts of rapid socio-cultural and political-economic change requires urgent attention, the knowledge and capacity available to carry out and analyze such research, train doctoral scholars, and to advise on policy-relevant questions remains a critical gap within the country. As anthropologist Dorji Penjore notes, “if the Bhutanese education planners had exercised their foresights, anthropology, not sociology, should have been a more useful course to study Bhutan, a nation of villages and farmers… If anthropology is the study of human culture and the hallmark of Bhutan’s nation is founded on the national goal of preserving and promoting its unique cultural identity, how paradoxical it is that the anthropology is neither taught at the Bhutanese colleges nor is there a formal anthropological study of Bhutan”. Currently, there exists no doctoral program in anthropology in Bhutan. Within such a context, ethnographic research is extremely rare and the discipline is exceptionally under-represented while facing highly limited resources for its development. At the same time, this gap also represents an important and timely opportunity to develop a doctoral program in anthropology in Bhutan. This is especially pertinent at a time when the demand for a doctoral program in anthropology is increasing with a small critical mass of senior anthropologists who can support such a vision.

Is anthropology a subject that attracts students in Bhutan?

Francoise: Students in Bhutan are starting to be interested by anthropology as they see it as a way to understand aspects of their culture and provide leads on social issues. However they do not have the luxury to study it as an intellectual topic and they will need to use it to gain employment.

Ritu: This is very much the case. Given the unique importance that Bhutan places on culture, and especially cultural resilience and promotion, as enshrined in the conceptual framework of Gross National Happiness, the attraction to anthropology is strong. Also, given the incredible influence of Vajrayana Buddhism in the country, where spiritual and cultural beliefs intermingle in profound ways, anthropology holds a special place. Students who are exposed to concepts and methodologies of anthropology are captured by its history, its ability to represent indigenous voices, and the analytical depth of lived experience captured by ethnography. Through anthropology, they are exposed to different cultural practices, norms and beliefs from around the world. In a country that was isolated from the world until 1959, tuned into television and internet in 1999, and became the world’s newest democracy in 2008, this provides an incredible treasure-house of knowledge and engagement with the world. Although Bhutan values an alternative and middle path to development that challenges GDP, materialism and environmental degradation so often associated with conventional understanding of ‘progress’, this recent paradoxical exposure to the outside world, has also resulted in rapid socio-cultural changes. Anthropology provides a valuable field of knowledge and methodology to view, document, attribute meaning to and protect important cultural practices in the face of globalization. While unemployment rates in Bhutan are not high compared to other countries, when combined with rural-urban migration, rapidly changing cultural identities and economic changes, these issues are of growing concern, and finding jobs is something that increasingly concerns students. The few anthropologists who have obtained Ph.D.s, have gone on to hold important leadership, policy-making, research and tertiary educational positions in the country, thereby making important contributions to nation-building and shaping the country in significant ways.

Can you tell us about your department, its specialties and how the award will help your department as it moves forward?

Francoise: At CLCS Taktse (Royal University of Bhutan), the department of history and culture has a certain number of lecturers who teach different aspects of Bhutanese culture. Many have a MA but none have a PhD. Since the mid 2000’s, selected lecturers have been conducting field trips and documenting different aspects of the Tangible and intangible heritage of Bhutan in 2 districts (see www.bhutanculturalatlas.org) as well as recording rituals and writing articles about them in an ethnograhic way. They were provided with ad hoc training in research methodology. The Royal University of Bhutan is now encouraging lecturers to do research but many lack the training to go beyond purely ethnographic description so the award will be of immense help to establish an academic program which will first benefit to selected lecturers of the department. Once the lecturers get their Ph.D’.s, they will teach the program modules themselves and CLCS will be able to accommodate students and lecturers from other colleges as well as international students attracted by such a program in a unique country.

Ritu: Although CLCS does not have a graduate or a doctoral program in anthropology, the need for a doctoral program that supports high quality ethnographic research in Bhutan is urgent. The department regularly receives requests for Ph.D.’s in anthropology and has hosted international visiting faculty for talks, seminars and research in Bhutan since 2005. At CLCS, an existing program of culture and anthropology is housed under the History and Culture Department which includes the Centre for History and Culture headed by the Dean of Research and International Links. Introduction to Anthropology and Himalayan Anthropology are taught in the Bhutan and Himalayan Studies (BHS) program at the undergraduate level. The Department also has an Audio-visual Unit (AVU) which documents and archives ethnographic materials such as rituals, dances, and oral histories. The department has been carrying out ethnographic research since 2005 under diverse projects and programs in Bhutan. Given the lack of an institutional framework and financial resources to further the field of anthropology at the doctoral level, it has not been able to systematically develop this aspect of the college. However, it benefits from the valued support of its Deans and esteemed Board of Governors, and most notably, His Majesty King Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck, who is the Chancellor of Royal University of Bhutan, under which CLCS is a constituent college. The Director General of CLCS is strongly supportive and committed to the establishment of the doctoral program in anthropology. The Department has 26 full-time faculty with graduate degrees in history and cultural anthropology and with ethnographic fieldwork experience, two of whom are senior anthropologists. With the important support of the award, CLCS can now dedicate the expertise of senior anthropologists and resources for important enabling activities, for the development of such a program, given the critical gap that exists in the discipline in the country. The grant has also enabled the establishment of a significant partnership with esteemed anthropologists at the Department of Anthropology at the University of California Los Angeles (Dr. Akhil Gupta, Dr. Nancy Levine and Dr. Sherry Ortner), whose guidance, academic exchange and intellectual resources for the development of the doctoral program are invaluable.