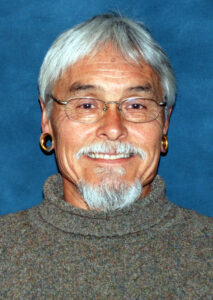

Interview: Dr. Joe Watkins of the National Park Service

Dr. Joe E. Watkins formerly held the position of Coca-Cola Professor and Director of Native American Studies at the University of Oklahoma. He has been involved with the Wenner-Gren Foundation for over a decade, participating in numerous workshops and conferences, and is now stepping into a new role with the National Park Service as Chief Supervisory Anthropologist of Tribal Relations and American Cultures. We got in touch with Dr. Watkins to learn more about his new position, the challenges it presents, and his thoughts on anthropology outside the traditional academy.

How did you get involved with the National Park Service?

Well, I applied for the job and was hired. It’s never that simple, of course. There were lots of other applicants for the position, and many of them within the Park Service system. I like to think I was hired based on my background as an archaeologist who practices social archaeology – I have always been interested in the relationships between archaeologists and the Indigenous groups with which they work (or don’t work), and know that much of what I do is anthropological archaeology. I look at the people in the past instead of just the archaeological material culture those people left behind. When I heard about the job offering, I thought it sounded like a challenge. The Supervisory Anthropologist position was challenging enough, but the newly formed Tribal Relations and American Cultures program seemed to offer an opportunity beyond the “normal” job of a federal anthropologist.

What exactly is the role that you’ll be stepping into?

I will be taking over the Tribal Relations and American Cultures program which oversees the Tribal Historic Preservation Officer (THPO) program, the Parks Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (Parks NAGPRA) program, and the Parks Ethnography program.

The Tribal Historic Preservation Officer program was established to help Native American tribes become fully partners in the preservation of historic properties on lands owned or controlled by the tribes. With more than 140 THPOs across the United States, the program helps strengthen tribal perspectives in the national historic preservation program. The Parks NAGPRA program was set it to help units of the NPS meet their statutory obligations under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990. Activities range from conducting inventories and summaries of collections under the control of NPS facilities to returning human remains and other particular classes of materials to Native American tribes. The Parks Ethnography program was established to help park superintendents and other Parks employees gain enough information about the people who have relationships with National Parks – either specific parks or the National Park Service in general. Uninformed Park superintendents run the risks of inadvertently making decisions adverse to particular sets of stakeholders – American Indians, local townspeople, and even tourists – which might increase conflict between parks and the American public, reduce support for NPS, and perhaps even legal suits.

What do you bring to it as an anthropologist?

Perhaps the primary thing I hope to bring to the job as an anthropologist is my ability to look at broad picture ideas that influence the relationships that groups hold with parks – Park managers need to try to manage limited resources for optimum return; American Indian groups often have relationships of past land use in areas currently encompassed by national parks but now precluded under Park policies; land owners around a Park have different relationships than those who do not have economic stake in the process. Visitors to the Park have a privileged relationship in many ways but are only there for a short period of time in comparison to the others. I believe it will be my job to provide guidance on differing perspectives and ways of dealing with the possible conflicts while at the same time trying to improve the Parks’ responses to the needs of the different people involved with the National Parks.

What do you think the future holds for anthropologists working in non-academic sectors?

I think working in the non-academic sector is perhaps the area of the widest and most rapid growth for anthropologists. The government sector always needs anthropologists because it has such direct relationships with people. Private industry also needs anthropologists to help them understand the various cultures they will encounter as globalization continues to occur. Social and cultural anthropologists can provide key insights into the human animal to help organizations better understand the complexities of inter-relationships and human thought. It definitely is a growing industry, regardless of what some uninformed politicians might believe.