Interview: Dr. Andrew Irving & “New York Stories”

Dr. Andrew Irving is Programme Director at the Granada Centre of Visual Anthropology at the University of Manchester. Recently he has been working on an experimental art/anthropology research project supported by a grant from the Wenner-Gren Foundation entited “New York Stories” revolving around questions of inner expression and lived experience in urban space. We had a chat with Dr. Irving to learn a little more about this unorthodox fieldwork and its relevance to the broader discipline.

I’d like to begin by setting the scene and learning a little bit about the project as a whole. Could you give a brief summary of your research in New York City? What were the aims of the project?

The original intention behind New York Stories was to extend my previous research that tried to understand the thinking and being of people close to death—especially in relation to the sometimes radical transformations that take place when confronting one’s own or another person’s mortality—for example, transformations in the perception of time, existence, religion, otherness and one’s body. This was for my original doctoral research in the late 1990s that compared living with HIV/AIDS in Africa and the USA.

At the time AIDS was seen as a death sentence, however the development of effective antiretroviral medications radically transformed people’s lives. Antiretrovirals re-opened time, space and society for over 100,000 people in New York alone, triggering a massive shift of mind, body and emotion across the city away from death and toward life. Having experienced intense, life-threatening episodes of illness and often having made irreversible life decisions, the people I worked with had to learn how to ‘live’ again but unsurprisingly many found it impossible to return to previous ways of thinking and being, and made substantial life style changes and career choices that affect how they live today. Thus the aim of New York Stories was to re-establish contact with persons from my original doctoral research to understand how they learned to re-establish their lives and maintain social and existential continuity while living in a future that few imagined they would survive to see.

How did you become interested in these questions revolving around interior expression?

Its been a long standing interest and one of the primary aims was to think about how all social life, including illness, is mediated by complex streams internally represented speech, moral commentary and imagery that are not always externalised or publicly articulated. Inner expression is central to experiences of illness and a primary means through which people understand their condition, negotiate periods of crisis and debate things such as suicide, that may not even be shared with close friends or family.

However a major new strand was introduced because one of the anonymous Wenner-Gren reviewers suggested the project needed to introduce a comparative perspective by considering the inner dialogues of the general population. I thought this was a very interesting idea but completely impractical and basically put the thought to the back of my mind. Then one of my main informants, a photographer and teacher called Frank Jump, who was diagnosed with HIV at 26 and told he only had a few years to live, made exactly the same point as the Wenner-Gren reviewer. This presented a huge challenge that is probably best expressed with a photograph.

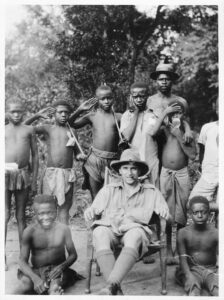

I have an extremely simple question about it that nevertheless places us beyond the limits of anthropology and even of science and human understanding itself. The question is what are these people thinking?

I have an extremely simple question about it that nevertheless places us beyond the limits of anthropology and even of science and human understanding itself. The question is what are these people thinking?

What for example is the woman in the right thinking? Or the man in sunglasses and the man behind him as they walk towards us? Or the man in the centre in the white shirt or in fact any of these people? What is the empirical content of their thoughts? As with any crowded city street, people may be engaged in diverse, or even radically different, forms of inner speech and imagery, with one person trying to remember if they locked their front door while others are respectively fantasising about an actor, deciding where to go for lunch, communing with a dead spouse or dealing with a major life change, such as having lost their job. Or as documented in Ethnography, Art and Death (Irving 2007) they might be walking around a city looking for a place to commit suicide, or have just received an HIV diagnosis and are confronting the uncertainty and contingency of their own existence in a public place (Irving 2009, 2010, 2011). In each case the person remains a social being and is required to act accordingly but their inner dialogues and lifeworlds are not necessarily made apparent to the wider world. Accordingly, the extent to which the people we see in streets, parks and cafes are engaged in the same practice remains an open question and reinforces the idea that the seemingly congruent social activities we observe in a city are differentiated by diverse modes of inner dialogue and expression that remain uncharted across the social sciences and are rarely, if ever, the focus of ethnographic research or anthropological monographs.

You experimented with a number of unorthodox fieldwork methods, many of which incorporated various pieces of fairly ordinary technology, such as cellphones. What was the process of developing these new methods? Were there any that were attempted, but later retooled or scrapped altogether?

I’ve been interested in experimenting with different methods in order to think about how different forms of inner expression—such as inner speech, unarticulated urges and desires, inchoate and non-linguistic forms of thought and much else besides—relate to people’s social lives, externally observable actions and material surroundings. As conventional social scientific methods are often too static to understand or represent the fluidity of inner dialogue and expression, especially when living with illness, social disruption or bodily instability, I’ve attempted to develop mutual research aims and methods alongisde the people I’ve been working with

The methods I used to get a sense of the general thoughtscape of New York City was very simple and I collected more than 100 interior dialogues of random strangers as they moved around the city. I divided the city into different zones of thought, eg streets, bridges, cafes, squares, transport, and I stood at different points in the city and asked people what they were thinking about in the moment immediately before I approached them. I then invited them to wear a small microphone and narrate the stream of their thoughts as they continued their journey or activity. I found it surprising not just the level of interest in the nature of the project but by the amount of people, from all walks of life, who said yes.

Below are 4 short videos of random strangers encountered in the city taken from the full-length recordings that range from 15 minutes to 1.5 hours.

The Lives of Other Citizens: STREETS

The Lives of Other Citizens: BRIDGES

The Lives of Other Citizens: CAFES

The Lives of Other Citizens: SQUARES

In terms of failure, obviously, there is no objective, independent access to someone else’s consciousness or experience—more colloquially put by Clifford Geertz as the impossibility of looking inside someone’s head—and so all the methods I’ve experimented with, including the one in the videos above are doomed to fail. But we also know that failure is essential to the creative process and also essential to research, fieldwork and understanding other people, and opens up all sorts of opportunities. The most recent method that was an out and out failure was an attempt to do simultaneous, choreographed ethnography in multiple places where I programmed all my informants cell phones to go off at random intervals during the course of a single day. The idea being that when the cell phones beeped people would record what they were thinking in that moment, and wherever they were, into the cell phone and also use the cell phone to take a photograph, but it didn’t really work because the technical aspect interrupted the stream of thought and by the time they had found the phone, switched on the camera app, fumbled with the recording button etc, the flow was gone and so I ended up getting lots of inner dialogues of people asking themselves technical questions and so forth.

What did you learn most about the participants?

As mentioned there is no objective access to consciousness (even if it’s our own consciousness, as Kant pointed out) but even in these short excerpts it is apparent that New York’s streets, cafes, bridges and squares are complex sites of experience and expression, that at times can be highly dramatic or theatrical, except we cannot see or hear the myriad inner dialogues that are going on underneath the surfaces of people’s public activity. The videos can only offer the tiniest glimpse into those realms of experience that can be articulated and approximated through words and images within a public, narrative encounter, and thus cannot claim to provide a comprehensive approach to people’s lived experiences of the city. Not all thought processes take place in language and routinely incorporate various non-linguistic and non-symbolic modes of thinking and being that operate beyond or at the threshold of language. The narrations are necessarily subject to many layers of self-censorship and the act of recording would have substantially influenced the content and character of the material in indeterminate ways. Nevertheless, as the person walked through the city narrating their thoughts it soon becomes apparent that there are as many ways of thinking as there are of speaking and by accompanying people on their journeys or as they sit in cafés or walk across bridges we are offered a glimpse into the different modes of internally represented speech, sensation, mood, emotion and memory that constitute the everyday social life and thoughtscape of the city.

Meredith’s thoughts in the video, for example, stretch from the trivial to the tragic over a few short steps as she begins by looking for a Staples stationary store to buy CD covers, then shortly after is dwelling on a friend’s cancer diagnosis she learnt about the previous night. Meanwhile, she looks over the road and notices a cafe she likes to watch people in. Thomas is concerned with people’s prospects in the current social and economic climate and his thoughts are organised as a sustained social analysis and argument about the position of working people and the historical migration of black workers from the agricultural south to the industrial north. It tells us a lot about the historical constitution of thought and consciousness and quite a few inner dialogues were explicitly linked to the global economic uncertainty and national security that has over-shadowed many people’s social lives since 9/11 and the banking crisis. Tony’s thoughts, as with many other inner dialogues I recorded, concerns the centrality of social and personal relations to everyday life. Tony is a writer and video artist, who walking to his house, his thoughts emerging in staccato bursts: as he walks quicker and his blood circulates faster he begins to get more argumentative with himself as he negotiates a significant life event and keeps returning to the same words suck it up or let it go.

As an anthropologist, perhaps the key things I learned were how difficult it is sometimes to “read” people on the street –or anticipate the content of their inner dialogues and existential state by outward appearance alone—and even though I had written about this in my work on suicide and so forth, the subject matter of people’s inner dialogues often came as a real surprise. I initially thought I would be able to guess which of the strangers walking along the street would participate but soon realised how bad I was at this. Whereas I imagined I would get lots of hipsters or artistic types to participate and virtually no-one else, in the end I got hardly any hipsters and found that a great diversity of people of all kinds said yes, making me realise how hard it is to read strangers. Even walking speed or appearing in a rush was not a reliable indicator of who would/not say yes. Importantly, you also come to realise the extent to which fieldwork is a performative practice that relies on one’s own body. Some days I would ask five people and four of them would say yes, other days I would ask twenty and only one would say yes. The most obvious variable in this was me, and how I used my body to approach people (especially as I’m tall, dark haired and look quite intense). It made me think of the classic fieldwork photos of Malinowski and Evans-Pritchard in the field and how their bodies must have been equally integral to the kinds of fieldwork data and evidence they collected and based their theories on.

A lot of the methods you employ, as well as the subject matter itself, might not strike laypeople as falling under the rubric of “anthropology” (it almost seems more akin to an art installation). For those who are confused, how would you explain your work’s connection to the concerns of the broader discipline?

The capacity for a complex inner lifeworld that encompasses ongoing streams of inner dialogue and reverie, as well as non-linguistic or image based forms of thought, is an essential component of being human and central to many everyday actions and practices. Simply put, without inner expression there would be no self-understanding or social existence in any recognisable form—and yet it is largely a terra incognita for anthropology or is seen as irrelevant or intangible—rather than an empirical phenomenon that is directly constitutive of people’s lives experiences and actions and worthy of investigation. As such anthropology is at risk of only telling half the story of human life.

Following anthropologists such as Michael Jackson, Vincent Crapanzano, Nigel Rapport, Daniel Lende, Henrietta Moore and Tanya Luhrmann, I would say that the problem is less with social-scientific methods or measures per-se but (i) narrow historical and disciplinary definitions of what is considered empirically admissible or worthy of investigation, and (ii) the tendency to categorise inner expression as a western, immaterial or literary phenomenon, rather than a fundamental phylogenetic capacity central to daily life and practice across the world. I think it’s fair to say that social-scientific disciplines have hitherto neglected to consider the crucial role of inner speech and expression in shaping people’s social, cultural and moral interactions, and in my case are methodologically unprepared to research how illness, crisis and other disruptive life events are mediated by complex realms of inner experience and expression that are not publically expressed.

This presents a deep-seated problem for disciplines like anthropology that are based on empirical evidence because it is primarily a methodological and practical problem rather than a conceptual one. In terms of fieldwork the problem is how to capture the transient, stream-like and ever-changing character of people’s interior expressions and experiences as they emerge in the moment. Early modernist writers such as Dostoyevsky, Joyce and Woolf actively strove to reconstruct and represent the complex but hidden inner conversations and lifeworlds that accompany social life, and to achieve something of the ‘humane significance’ of art, Rodney Needham argued that anthropologists should try to write with the introspective insight and perspicacity associated with the modernist novel. However there is a crucial difference of course in that unlike poetic, literary, or artistic attempts to understand and represent people’s interior dialogues and streams of consciousness, an anthropological approach to interiority has a duty to offer truthful and empirically justifiable accounts of people’s experiences, thereby raising significant epistemological, methodological, and ethnographic problems. In other words, furthering understanding about the role of internally represented speech in social life (or illness) needs to be grounded in empirical data across a range of lived experiences rather than addressed speculatively or by abstract theory alone.

By bringing a detailed ethnographic focus to this field, I’m hoping that the kinds of art/anthropology project I’m engaged in here will open up a new research area and provide an opportunity for a critical rethinking of the ontological and evidential status accorded to people’s experiential interior within social-science and anthropology. For my main research area this means how people across a range of social, cultural and religious groups, use inner speech to cope with serious illness and crisis, psychological and bodily disruption, establish continuity and make critical life decisions.

But at the same time I’m getting more and more interested in the everyday urban life side of things that were unexpectedly emerged and opened up in this Wenner-Gren project. I also think there’s an audience for this kind of anthropological project beyond the academy, as I haven’t really started writing this up for publication and yet its already been reported on by Scientific American, NPR, Voice of America, the Village Voice and in Europe and the UK, while the videos, despite being on the experimental side of anthropology, have been watched by thousands of people per day, showing that there is a substantial public interest and appetite for anthropology out there.

What’s next for this research? How might you see this project expanding in the future?

I am thinking of constructing a 2.5 mile x 2.5 mile piece of Sonic Ethnography in downtown Manhattan where I collected most of the dialogues that will use, as its initial database the 100 inner dialogues of strangers that I recorded for this project. I’ve been collaborating with an electro-acoustic composer and an app designer in order to make a custom designed LOC app for the project that will run on apple/android devices. This will mean that the inner dialogues can be downloaded (via the LOC app’s GPS Locative-Audio) onto the exact co-ordinates of the original locations where the dialogues were recorded. This will enable anyone with a smart phone and the app in the physical vicinity of the Sonic Ethnography to live-stream and access the thoughts of other citizens. The LOC app is will be designed to incorporate 3D directional audio technology, which means that as people turn their heads, change direction, move their bodies in space etc., they will automatically hear different inner dialogues and locate where they coming from. This will allow for body movement to act as a ‘live mixing’ system of other people’s thoughts as the person moves through the city. It is also possible to make the Sonic Ethnography dynamic so that the LOC app’s Dynamic Content Server will automatically evaluate environmental variables (such as time of the day/night, commemorative days, atmospheric conditions, weekends) so that different databases of inner-dialogues become triggered that reinforce/play against time, rhythm, weather, quality of light etc. I’m obviously based in Manchester but I was actually considering applying for a Wenner Gren Engaged Anthropology grant to construct and run this Sonic Ethnography over the summer next year in New York so that citizens and tourists of New York alike would be able to wander around the city with someone else’s thoughts in their heads and engage in an anthropological understanding of the city.