Interview: Aisha Ghani and the Difficulties of Terrorism Discourse

Aisha Ghani is a Ph.D. student in Anthropology at Stanford University. In 2011 she received a Dissertation Fieldwork Grant to aid research on ‘Conflated Identities: ‘Muslim’/’Terrorist’ and the Difficulty of Producing a Genuine Discourse about Terrorism,’ supervised by Dr. T. M. Luhrmann. We chatted with Aisha over e-mail to learn more about her fieldwork in the courtrooms of U.S. domestic terrorism trials and the role that legal proceedings play in shaping national terrorism discourse.

Tell us a little about the project that you’re working on.

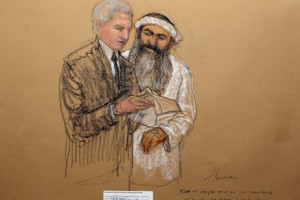

Through observation of courtroom proceedings and case material in domestic terrorism trials and Guantanamo and Bagram detainee litigation, I examine how the Global War on Terror (GWOT) is imagined, articulated, challenged and reinforced in various kinds of U.S. Courts. I ask how the state’s “foundational” discourse in the Global War on Terror has 1) shaped and limited the nature of legal challenges that can and have arisen in courts, and how the discursive limits of the litigation have 2) worked in determining the kinds of ‘terrorist’ subjects who are called upon – and can call upon – the law. A crucial element of my research involves observing the ways in which ideas about Islam — including the Muslim sociality and subjectivity of accused terrorists– enters into legal spaces. What is the work of these socio-religious claims, and how do they relate to the legal and political claims being articulated in and through these cases? How do accused men, if and when given the opportunity to speak, choose to situate themselves in relation to the explicit and implicit legal and political claims of the state in the GWOT?

Outside of courtrooms, my research involves ethnographic interviews with family members of accused and convicted men, as well as interviews with lawyers and civil rights activists involved in litigation and/or advocacy efforts around particular cases and broader national security law and policy issues after 9/11. In engaging with these different kinds of people, I attempt to understand the ways in which their narratives of experience and public advocacy efforts, destabilize and nuance the meta-narratives of the state with respect to what Islam is, what terrorism is, and who accused men are, in ways that cannot perhaps be achieved through the language and processes of the law.

Could you talk a little about what inspired you to choose this particular field site and topic?

Like many anthropology students, I entered graduate school imagining that my research would take me outside the United States. Implicit in this idea, in my case, was the assumption that ‘culture’ exists in ‘Other’ places, and not here. As I progressed through the program, a growing realization took place: there was plenty of anthropology to be done in the United States. For me, the U.S. became increasingly compelling as a field-site in relation to the War on Terror, which – it was clear by then – was here to stay, and expanding daily. How were we to understand its existence and expansion despite looming questions concerning 1) the legality of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, 2) the legality of U.S. administered detention and proxy-detention all over the world, and 3) growing evidence of U.S. sanctioned torture? The legal and political contestations around these questions belied a tension that ultimately drew me to this topic and field-site.

Additionally, I decided to focus on legal cases and the sociality around them, after arriving at the realization that while there was growing work in anthropology that critically engaged with issues like Human Terrain Systems and counter-insurgency (COIN) policy and literature, there was less of an ethnographic focus on ‘sites of terror’; that is, sites inhabited and determined by real and imagined ideas about terrorism, including: war zones, courtrooms, Mosques and other kinds of Muslim spaces. Lastly, there also seemed to be a need for ethnographic work that attempted to grasp something of the experience of those directly affected or implicated by law and policy in the Global War on Terror.

You have attended a number of terrorism-related trials and proceedings for your research. What struck or surprised you the most about these sites?

When I began observing “terrorism” trials, one of the very first things that fascinated me was the way in which the courtroom was ritually prepared, through a set of security measures, for terrorism trials. In each of the seven terrorism prosecutions I’ve observed, enhanced security measures have been taken. These measures include the very visible presence of between 5-10 U.S. Marshals who belong to the Special Operations Group (SOG), and are designated to oversee terrorism-related court proceedings . They dress in suits, are armed with guns, and line the gallery of the court, standing or sitting behind visitors of the court and beside defense and prosecuting attorneys. According to their website, U.S. Marshals are tasked with providing:

protection of the judicial process – by ensuring the safe and secure conduct of judicial proceedings and protecting federal judges, jurors and other members of the federal judiciary. This mission is accomplished by anticipating and deterring threats to the judiciary, and the continuous development and employment of innovative protective techniques.

Another acknowledged role of the U.S. Marshals is ensuring the “protection of visitors of the court.” The language of protection is interesting, particularly in terms of what it elides. For U.S. Marshals, “innovative protective techniques” can include what is termed “unobtrusive surveillance” of the courtroom. It’s not entirely clear how unobtrusive is imagined and defined by the U.S. Marshals but, based on my observation, it is purposefully obvious.

I observed a particularly illustrative example of unobtrusive surveillance at a terrorism trial I attended before the Eastern District of New York (EDNY). At the time of this particular trial, I was midway through my field research and had therefore attended court in a handful of cases. Given this, I had come to anticipate questions from reporters and U.S. Marshals — questions most often elicited in response to my sustained presence in the courtroom and, I will admit, copious note-taking. The questions have generally been limited to inquiries about who I am and what I do, and are presented to me as innocuous, harmless small-talk or ‘natural’ curiosity. During the trial, I was approached by a group of U.S. Marshals on the second day while court was in recess for lunch. The Marshals asked me the aforementioned questions and I obliged by answering them. Given the exchange, I did not anticipate being approached for remainder of the trial. However, on the fourth day of the trial, a U.S. Marshal approached me and asked, or rather told me, to stop taking notes. He said that there was some concern, stemming from the prosecution, that I was “transcribing” the legal proceeding, and that I was doing this in order to relay information to a key witness – the daughter of the defendant- who had yet to testify. Given the accusation – and I certainly experienced it as such – I can only assume that I had been (mis)identified by the prosecution as someone who knew the defendant in the case; I did not, but even if I had, the association did not, in and of itself, serve as justification for the accusation. In any case, I had been marked as suspicious, a potential threat to the judicial process that the U.S. Marshalls were supposed to be protecting.

I responded by denying the accusation and refusing their request to stop taking notes. I also reminded the Marshals of their other declared purpose: to ensure the protection of visitors of the court, a protection which, as I stated “ought to include protecting my rights.” That this rather basic act of resistance was successful in suppressing the issue indicated to me that the U.S. Marshals (and government’s attorneys) had anticipated compliance simply because “they said so.” The experience returned me to Kafka; reminding me of the power of authority to sustain itself, even in the absence of explanation. And that the courtroom – an ostensibly legal space – served as the site for this excess is striking, even if it is not, following Kafka, surprising.

In addition to the guaranteed presence of U.S. Marshals, entry into the courtroom in high-profile terrorism cases sometimes requires presenting ID’s and “checking in” to the courtroom. Collectively, these practices can act as deterrents, discouraging public attendance. Many of my subjects have described these measures as intimidating; they consider themselves a vulnerable demographic as Muslims in a post-9/11 world, and these measures invoke ambivalence and anxiety. They know that the decision to attend court involves risks, including providing the government with a record of their names, and that entrance into the courtroom will be interpreted as ‘willful’ subjection to the possibility of ‘unobstrusive’ surveillance.

At a theoretical level, these precautionary measures reveal a certain irony: the alleged threat of terrorism that it is, at least theoretically, the function of the trial to ascertain the validity of, is being reinforced prior to, and in the absence of, legal judgement. For these security measures anticipate and, in anticipating, reproduce the idea of terror through the corporeality of the accused, and through the threat that is imagined as being posed by the kinds of people who would be compelled to attend court in such a case.

I cannot speculate about the precise impact these security measures have on jurors, but it is worth noting the emergence of a certain contradiction here: On one hand, potential jurors are subjected to a process known as voir dire, during which they are asked about their backgrounds and any existing relationship or opinions they have with respect to the case, thereby vetting them for potential biases. Through this process of distillation, the court imagines itself as fulfilling its constitutional promise: providing the defendant with an “objective” jury of his/her peers and, therefore, access to a fair trial. So, on one hand, there is an insistence on constructing the courtroom as a kind of pure space that jurors will enter into as “post-modern strangers” (to borrow from Julia Kristeva’s language). On the other hand, the security measures in terrorism trials create a circumstance whereby jurors, a group of carefully selected arbiters of justice, will enter into a courtroom that openly expresses its relationship to terrorism. A certain undoing of the legal promise takes place, and yet courts do not recognize, or perhaps care about, this contradiction, nor the ways in which the measures engender the possible production of biases on the part of jurors.

What do you think has changed the most about American discourse concerning terrorism over the past ten years? How can anthropologists contribute to or further understanding?

There are a lot of ways to answer this question, but allow me to provide one example that strikes me as particularly useful, especially because of the way in which it highlights the importance of, and necessity for, anthropological analysis.

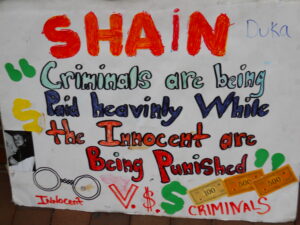

In my research I’ve been astonished by how much attention and effort the government places on the question of violence, and how terrorism has been constructed as a category that indexes a particular form of violence, primarily defined by who enacts or attempts to enact this violence, and the kinds of networks (foreign terrorist organizations (FTOs)) through which its possibility surfaces. Amongst civil liberties groups, activists, and the near and dear of accused men, on the other hand, the question of violence often does not get taken up. Instead their focus is on rights, and highlighting the “erosion of civil liberties” that is taking place through heavy-handed and disciminatory law and policies. This makes sense in all sorts of ways, as much of the efforts of those in this second group, are focused on dismantling and challenging the substance and pervasiveness of the link between Islam, violence and terrorism. But these competing incentives also have a cacophanous effect; a certain incommensurability emerges between the government and those attempting to challenge the government’s discourse because there is no clear stitching point between these conversations. In all of this, however, the concept of violence, as an analytic, becomes difficult to address unless one steps away from the interests and imperatives of both groups. There appears to be something equally purposeful, generative, and enabling about the government’s focus on violence, and its omission amongst civil libertarians.

And yet, the question of violence requires attention, not only because the circumstance I have described are anthropologically interesting, but because the very men whose cases I follow in court often centralize and position themselves in relation to the concept of violence. And they do not always do this in order to evade its accusation, but rather, in order to seek recognition of that violence as a justified and just course of action. These fissures and contestations in discourse production and self-making processes are of central interest to me as an anthropologist, not only because nuancing the discourse of terrorism is important, but because, in the case of terrorism discourse, nuancing is in and of itself a shift.

This is where anthropology becomes central, in my opinion. Not only because anthropologists are interested in these shifts, how they come about and why, but because anthropologists are interested in asking questions that present the possibility of nuancing and shifting discourse, too. In my work, I have found that the kinds of questions I am interested in as an anthropologist are often similar to those of the people whose efforts and lives I am invested in understanding, but they are also, just as often, different. I’ve found that the distance between our interests can be just as generative as the intersections, as some of the most compelling (and pressing) questions emerge at the limits of intersectionality.

Are you a current or past Wenner-Gren grantee and would like to be interviewed for our blog? Contact Daniel (dsalas@wennergren.org) for more information.