Fejos Postdoctoral Fellow: Gaspard Renault

The desire to make a film grounded in long-term ethnographic research emerged nearly a decade ago. After graduating in film studies in 2009, I worked for several years as a lighting and camera operator while aspiring to direct my own documentary projects. I became particularly drawn to visual anthropology for its immersive, collaborative, and field-based approach, as well as its deep historical ties to documentary filmmaking. In 2016, I began a multispecies, multisited visual ethnography of wildlife rehabilitation practices in Bolivia, in collaboration with the Bolivian nonprofit organization Comunidad Inti Wara Yassi (CIWY).

CIWY originated in the late 1980s with a training program for street children in El Alto, near La Paz, and gradually incorporated nature and wildlife conservation throughout the 1990s. Today, the organization operates three wildlife rehabilitation centers where animals affected by illegal trafficking, urban expansion, and forest fires—such as capuchin and spider monkeys—are rescued and cared for by Bolivian and international veterinarians, biologists, and professional and volunteer caretakers.

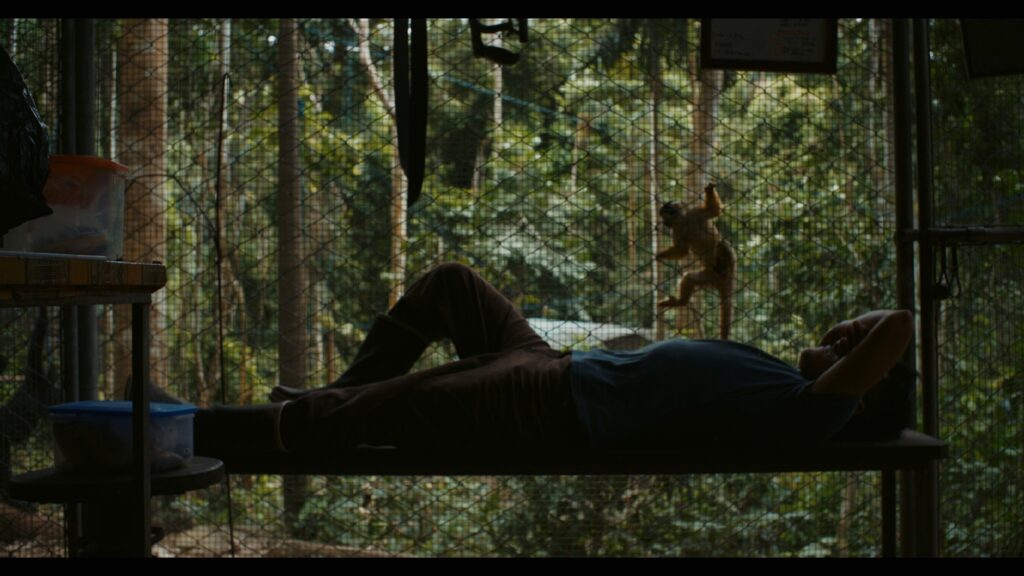

It was during this research that I met Rusber. He was eight years old when Nena, CIWY’s founder and president, adopted him after he had spent two years living on the streets of Cochabamba. He grew up in and around Machia, CIWY’s primate rehabilitation center and administrative headquarters, and gradually became one of its most committed caretakers. One day, while accompanying him into town, I asked about the circumstances that had brought him to CIWY. He spoke of his parents’ alcoholism, his father’s abandonment, the accident that killed his mother in front of him, and his years surviving on the streets. He recounted with humor the odd jobs he did to eat, the day he fell asleep on a bus and woke up surrounded by tropical forest, his first meeting with Nena, his fear of working with monkeys, and the sense of indebtedness he now feels toward those who welcomed him as family.

Rusber’s story resonated deeply with Donna Haraway’s idea of “becoming with” another species. For him, bonds of kinship are not defined by blood or species, but by shared histories, daily care, and mutual dependence. As he told me, “these monkeys are my brothers; their journey mirrors my own.” It became clear that through caring for animals, Rusber was also shaping his own life, and that this process could provide the emotional and narrative core of a film—one capable of expressing something beyond the scope of conventional academic writing. This intuition became even stronger as CIWY entered a pivotal period in its history, coinciding with a turning point in Rusber’s early adult life.

In 2021, after successfully defending my doctoral thesis and writing a first film treatment, I returned to Bolivia as a cinematographer to present the project to Rusber and Nena. At that time, the Bolivian government had approved the construction of a highway that would expand the road in front of Machia, threatening the shelter’s existence. CIWY decided to relocate all animals to Jacj Cuisi, a more remote site in northern part of Bolivia. This required financing and building new infrastructure before transferring animals group by group across the country. The scale and urgency of this operation provided a strong narrative framework for the film.

For Nena, the film could also serve as a tool to promote CIWY’s work during this challenging transition. For Rusber, it seemed to respond to a need to preserve a trace of the place where he had grown up. The closure of Machia and the relocation of the animals also prompted him to reconsider his own future within CIWY, and he was open to using the filmmaking process as a means of reflection.

In December 2021, with their approval and initial funding secured, I filmed the transfer of the first group of spider monkeys. This shoot helped refine the film’s aesthetic direction and production needs, leading to a second shoot in February 2023 with a Bolivian crew. By then, Rusber was living at Jacj Cuisi, overseeing the monkeys’ adaptation to their new environment. Returning briefly to Machia, he expressed his wish to complete the final semester of his veterinary studies, interrupted during the COVID-19 pandemic. He hoped to graduate, find an internship or job with another organization, and possibly travel abroad. These emerging aspirations, combined with Machia’s relocation and the highway construction, shifted the film’s narrative trajectory.

A third phase of filming took place in December 2024 during Rusber’s final week at the veterinary faculty of San Simón University in Cochabamba. Away from the daily pressures of wildlife rehabilitation, he appeared more willing to question his relationship with Nena and his role within CIWY. We filmed him attending classes, meeting new friends, and revisiting the places where he had lived on the streets. As he trained in livestock medicine, he reflected on his ethical convictions and those underlying the veterinary profession more broadly. Meanwhile, widespread forest fires and Nena’s growing exhaustion underscored the urgency of his training and drew him back toward his responsibilities within CIWY.

At this stage, it became clear that the central question was no longer whether Rusber would leave CIWY, but how he would reconcile his personal aspirations with his loyalty to Nena and the animals. The film’s narrative focus shifted accordingly.

By fall 2024, support from the Wenner-Gren Fejos Postdoctoral Fellowship and other funding sources enabled preparation for a final shoot, intended to document the transfer of the last group of capuchin monkeys from Machia to Jacj Cuisi. However, severe fires, heavy rains, and political and economic instability delayed construction at the new center. Faced with production deadlines, we proceeded without filming the relocation. This allowed more time at Jacj Cuisi to focus on the everyday practices of care. We filmed Rusber and the staff integrating new monkeys into the existing group and reflected on his personal evolution throughout the project.

Over four years, the project comprised approximately 30 shooting days and 80 hours of footage. Postproduction began in April 2025 in France and concluded in late June. Editing lasted six weeks and benefited greatly from editor Morgan de Laporte’s familiarity with the material. Although time constraints limited experimentation with alternative narrative structures, feedback from producers, specialists, and non-specialist viewers helped refine the film’s dramatic balance.

The original score was composed by Casual Melancholia, built around a piano and cello theme for Rusber, complemented by symphonic pieces evoking environmental elements. Sound editing and mixing were handled by Marco Pascal, and color grading by Axelle Gonay.

Since 2021, the project has been supported by Sharing Productions, which holds the film’s commercial rights. Our aim is to reach broad audiences, both academic and non-academic, particularly in Bolivia. The film has been submitted to major festivals and will premiere on Ushuaïa TV in spring 2026, followed by a broadcast on Lyon Capitale TV. Copies will be provided to CIWY for outreach purposes, with screenings planned in Bolivia, including at the French Embassy in La Paz and CIWY’s rehabilitation centers. The project is sponsored by the Jane Goodall Institute France.

Finally, the film will accompany a forthcoming multimodal essay published by the Presses Universitaires de Lyon, combining fieldwork materials, unused footage, and critical analysis. Together, the film and book form a reflexive proposal for a multispecies anthropology through and by film.