Fejos Postdoctoral Fellow: Diana Allan

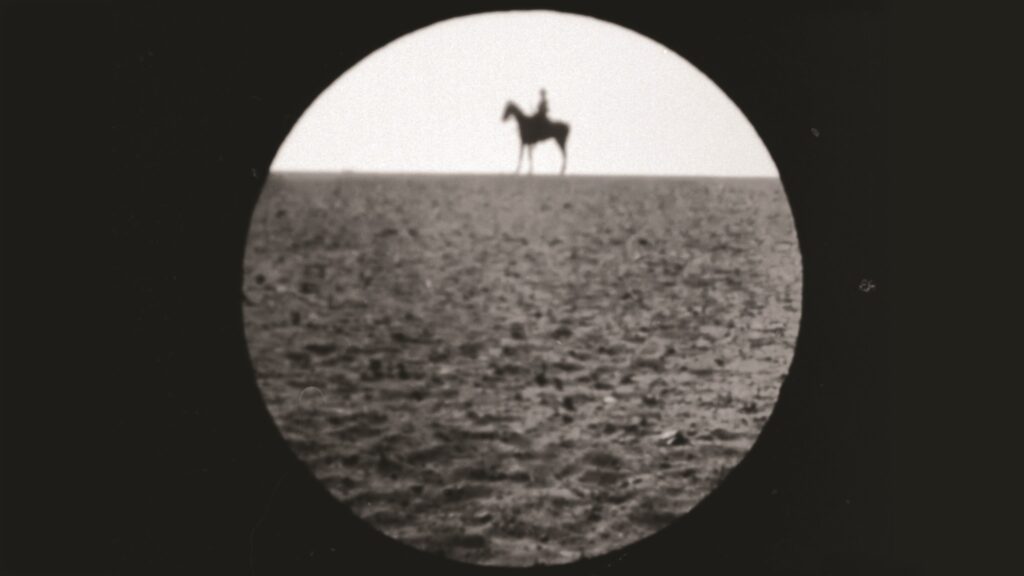

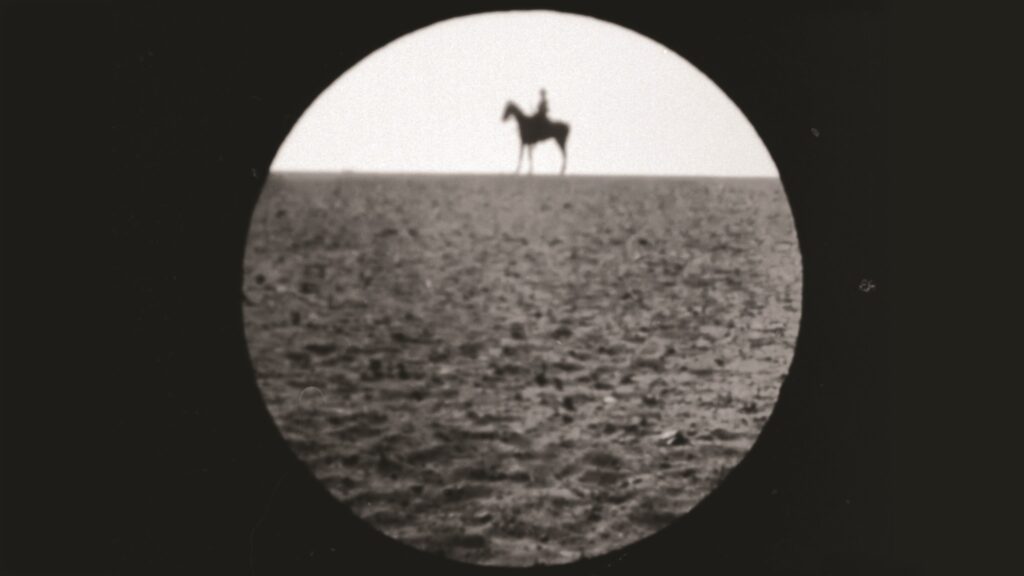

Partition is a found footage film that brings together materials from the British occupation of Palestine, roughly between 1917-1948 (newsreels, recruitment films, government propaganda, and films shot by the British army film unit), with a palimpsestic audio track (songs, interviews, ambient sounds) that I have recorded with Palestinian refugees in Lebanon and elsewhere over many years. Additional archival sound was drawn from two BBC Radio Palestine broadcasts recorded during the last days of the British Mandate in 1948. The film grows from my ongoing work––ethnographic, archival, activist, and filmic––gathering stories of Palestinian exilic experience in Lebanon, and brings forms of sensory and synesthetic attention developed in documentary filmmaking to bear on colonial images and narratives. My aim in this film has been to stage an encounter between ways of knowing and telling, and to invite viewers to consider how stories are told, truth claims are made, histories delineated, and archival materials are both “found and constructed, factual yet fictive, public yet private” (Foster 2004, 5).

In exhuming and reworking these colonial films for Partition, the film also implicitly challenges forms of archival exclusion that inhibit Palestinians from accessing the material traces of their own past. They doubly dispossessed––not only of land, but also of the records of their history, which are held in colonial institutions. In a very real sense, these imperial archives do not own the images of colonized subjects in their collections. Rematerializing through rephotography and sound also kindled my interest in how altering and intervening in these colonial images—through cropping, reframing, enlarging, altering their duration, and hand processing techniques––allowed for different kinds of relation to the archival images to form. In this sense, the footage was never exactly “found,” but continually reimagined and remade through engagement and sonic animation; these images are not static, but dynamic and responsive. Having now worked with these images, intermittently, over several years, I recognize their life and agency. They take up residence in the mind of the viewer and haunt; ghosts have continued to appear in these images across the various stages of production. The unexplained “glitches” and artifacts that have appeared in the images have become a structuring element of the film itself. It sometimes felt as if the images could no longer contain the experience they held.

Partition is more formally experimental than my previous films. It employs dialectical montage and asynchronous sound as a method through which to deconstruct and reconstruct colonial images, and explores the experience of Palestinian displacement and dispossession as a form of life. The film is animated by a line of critical inquiry with several key nodes: (1) rethinking the archive—as abstract institution and as actual “holding”; (2) the dialectical meanings that emerge from visual and sonic representation; (3) the shifting interaction between analog and digital technologies; (4) the productively unsettled status of the archive—as living and revisable as opposed to inert and fixed; (5) and the reframing, reconfiguring and re-activating of the archive in the service of counter-narratives. It asks several overarching questions: How can colonial pasts and imperial seeing be unraveled through the soundscapes of a radically unstable Palestinian present? What continuity of presence do Palestinian voices make visible in these colonial images today, and how might listening disrupt an overdetermined politics of looking? In the course of engaging with histories of Palestinian expulsion and exile over several decades, I have become increasingly attentive to the embodied registers of remembrance held in voice––what Dolar calls the “vocal fingerprint” (2012), which communicates a felt relation to people, place, and time, and projects the preoccupations of exilic life forwards. Emerging from conversations and stories shared around the hearth of my laptop, Partition leans into these immersive registers of refugee expressivity––elegiac, inventorial, performative, poetic, defiant, celebratory––that enact, formally, the rhythms of dislocation and reintegration structuring refugee life as “both sensible and sense-making” (Sobchack1992, 7).

Working on this film intensively over the past year made vivid the recursive forms of extreme violence that structure Palestinian life. The obliteration of Gaza is, for all its horror, a familiar iteration. We recognize in it a form of dispossession that is less event than condition, an asymptotic arc forever approaching the horizon of erasure. What can colonial images from British occupied Palestine tell us about events today? What line of continuity might be drawn between the colonial and imperial forces at work, then and now? How does the ambiguous relation of figure and ground shift again? What is foregrounded, what recedes from view? Silent images gathered in imperial collections hold histories that have barely been told. In recent weeks, I’ve found myself thinking of Ursula LeGuin’s, “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction” (1986) and how it speaks to this idea of figure and ground in Partition, as well as to gender and time. While colonial films sought to instill racialized pattern recognition and relation, if we set aside what LeGuin calls the linear “Techno-Heroics” and view colonial images not as spears that dominate but containers that hold––the “thing to put things in”––another form of realism emerges. The Palestinian figure rises again from the colonial ground, brought back to life through voice, story and song.

Partition was completed in December 2024 and premiered at the International Film Festival Rotterdam (January 2025). It will also screen at Cinema du Reel (March 2025) and at the Margaret Mead Film Festival in New York (May 2025).