Introduction

The project submitted to the Engaged Research Grant proposed a collective writing and publication of five books by women of the Recôncavo da Bahia, Brazil. The call format enabled the research to be carried out not only by me, the anthropologist, but also by the women with whom I built knowledge throughout the year, who became the authors of their books.

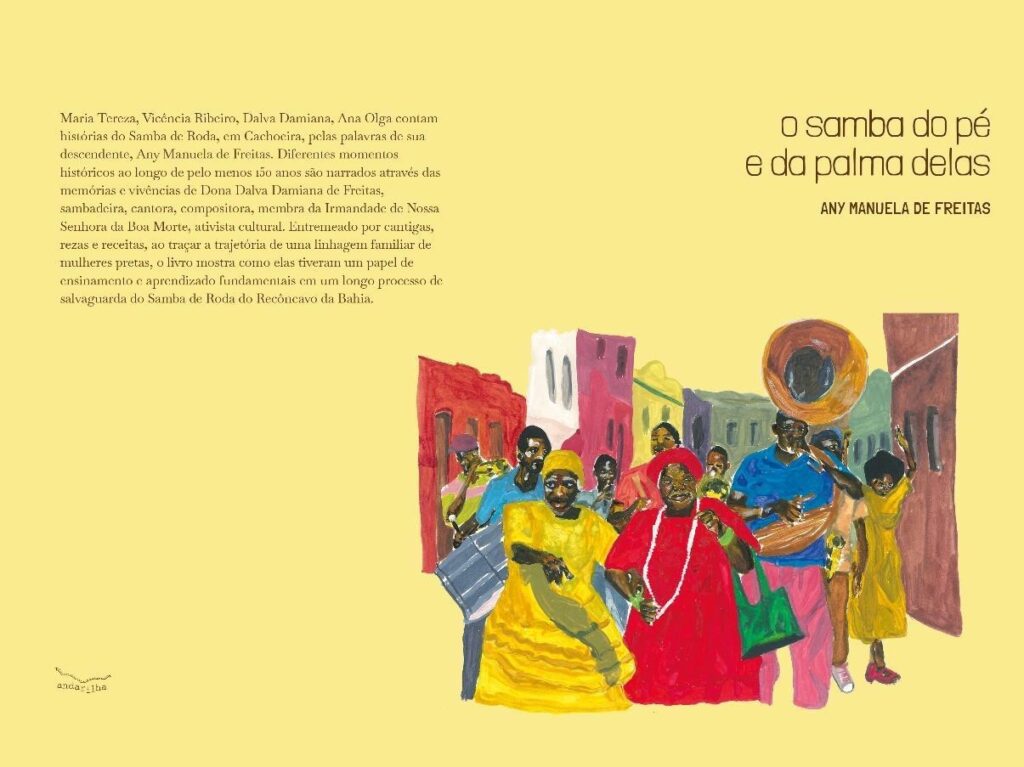

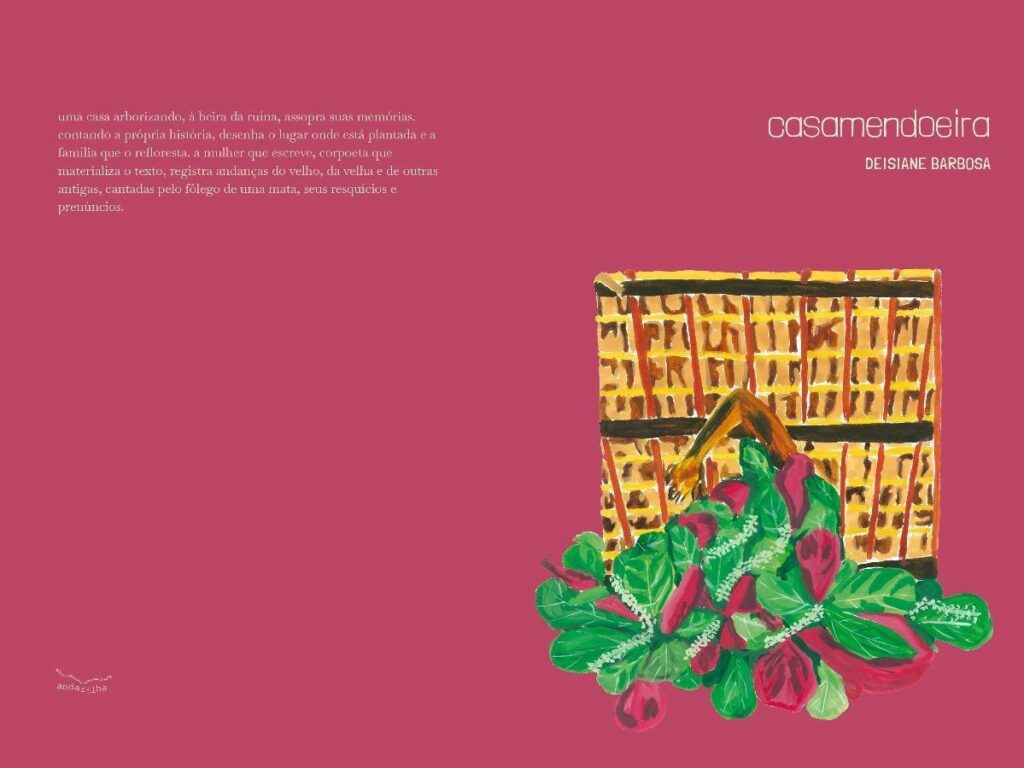

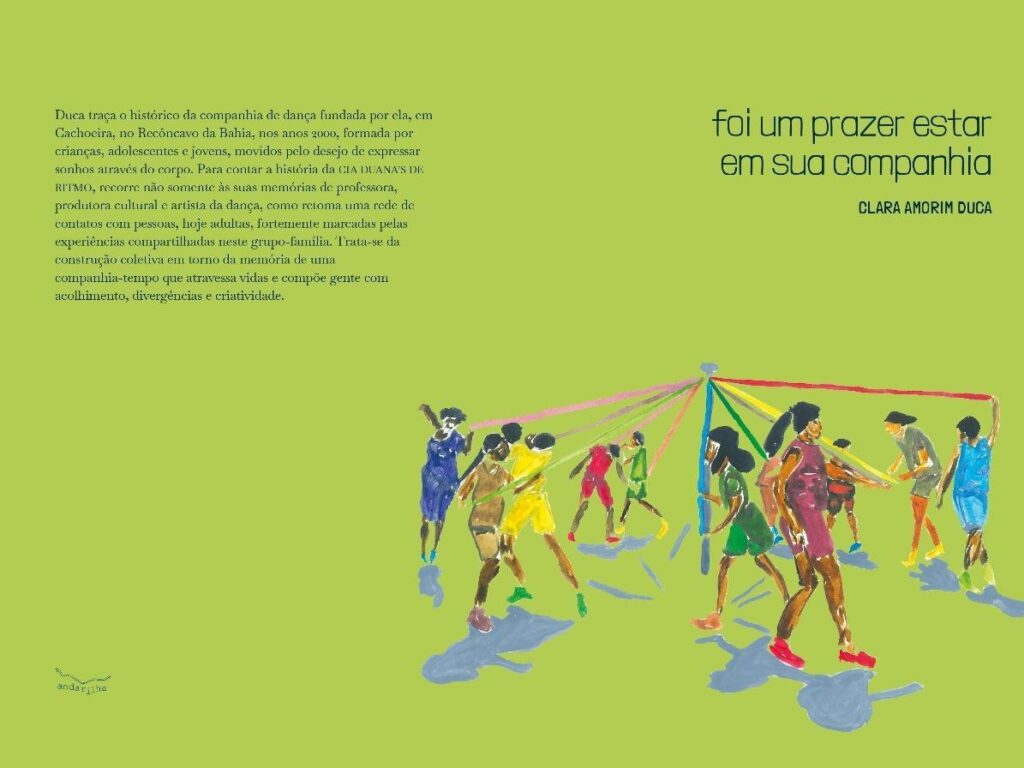

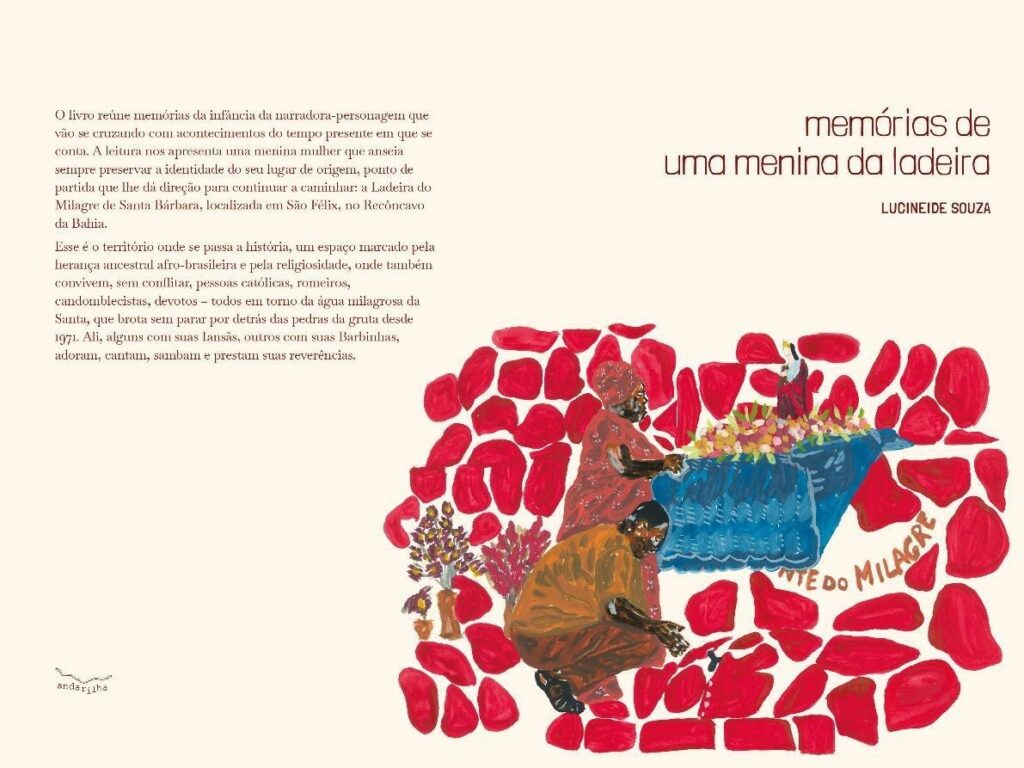

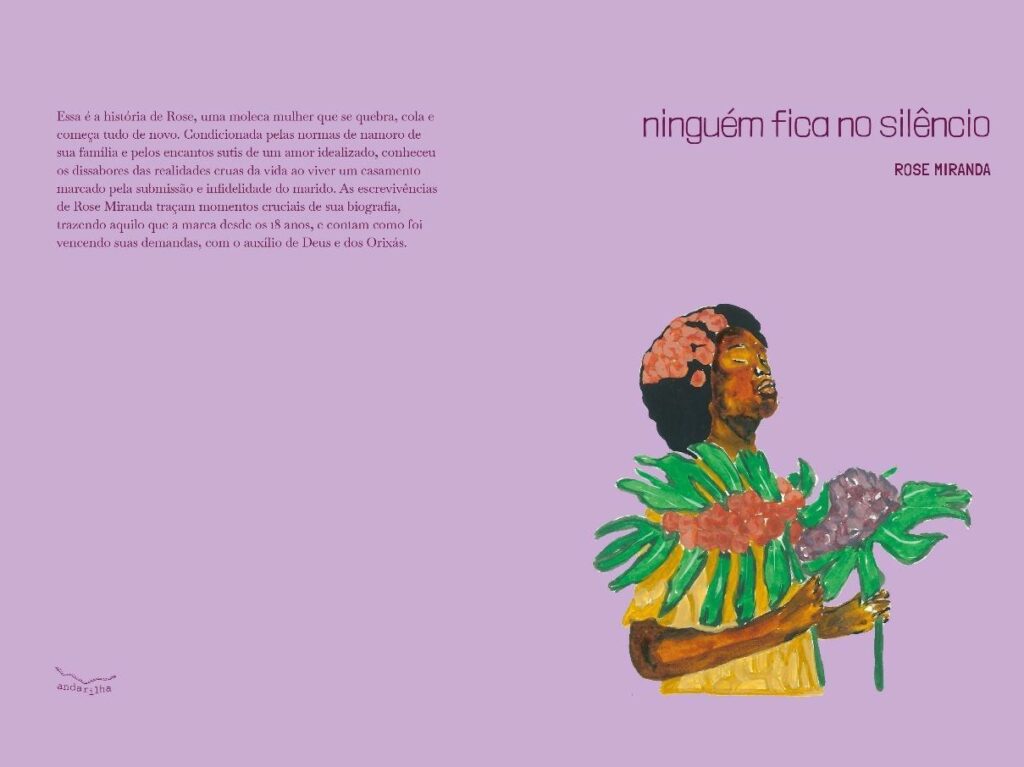

From the position of editor, more than co-author as a researcher, we constructed quite different narratives of the region’s official historiography, generally made by an economic point of view and from the perspective of a white elite heiress of sugar mills and plantation (VALE, 2018). The Recôncavo da Bahia thus was retold in stories about the culture and dance scene in Cachoeira (Foi um prazer estar em sua companhia [It was a pleasure to be in your company], Clara Amorim Duca, 2023); the tales of Ladeira do Milagre and Gruta de Santa Bárbara in São Félix (Memórias de uma Menina da Ladeira [Memoirs of a little girl from Ladeira], Lucineide Souza, 2023); how the Dona Dalva’s Samba de Roda was created and its relationship with the trajectory of black women from the Recôncavo in the struggle for the transmission and preservation of this intangible heritage (O samba do pé e da palma delas [The samba of their foot and palm], Any Manuela Freitas, 2023); the autobiography of an adobe house intertwined with the stories of an tropical almond tree and the family that planted-built them, in a Recôncavo marked by the production of cassava flour on casas de farinhas [adobe houses for cassava flour oven] (casamensoeira, Deisiane Barbosa, 2023); and the path of a woman with fome de conhecimento [thirsty for knowledge] who faced a marriage that did not allow her to spread her wings (Ninguém fica no silêncio [Nobody stays silent], Rose Miranda, 2023).

In this report, therefore, I present an initial proposal for reflection based on the engaged research carried out between March 2022 and April 2023. Based on the discussion of the geopolitics of bodies in academic knowledge production and the quilombola literature, writing here is a disputed territory. The idea of social technologies of common (JÚNIOR et al., 2021) also helps us to think about collective strategies for writing and occupying hegemonic places in academia by “others” bodies, such as black women from the Recôncavo da Bahia. I also describe the methodology of the Cachoeiras Project, the poetic uprisings (BARBOSA, 2020), and the collective writing process of the five books, reflecting on the editorial organization as a way of doing ethnography and producing knowledge. This discussion will be better developed and submitted as an article by me and Deisiane Barbosa for the journal Women and Performance, to be translated also with the Engaged Research resources.

Writing as a common

The great meaning for me in being part of this project is to leave a reference for the younger ones and a memory for the older ones taking the place of author / writer. I always thought I could never write a book. Being part of this group of authors tells me of the importance of disseminating the female and Bahian literary voice that is not valued by our society where the writing of white men prevails as the only and central reference. From this project I will be able to publish my first book, resisting in the body of a black woman in such an unequal, patriarchal and racist country, encouraging my equals and proving that we can indeed be writers, talking about us and our territory where we often live marginalized with the truths between the lines that do not count when they talk about us and we are not protagonists. (Lucineide Souza, 2021)

To submit the Cachoeiras Project to the Wenner-Gren Foundation’s Call it was necessary to present as documentation the letters of the people who would participate in the research. At that initial moment, these first lines from the authors already announced one of the main points that we would discuss in our meetings, the fact that they had difficulty in seeing themselves as authors.

In March 2022 we met for the first time as a group of authors. If at first they were shy, as soon as the word circulated, stories of their lives and possibilities of writing these experiences flowed, despite the uncomfortable use of a tool, the writing, which was always presented to them as something alien to their busy daily

routine. Between taking care of children, home, parents, work and studies, these women took the writing process as a new routine. Deisiane Barbosa and Lucineide Souza were an exception, the first was starting to write her fourth literary book and the second had already participated in creative writing workshops and published a short story in a collection resulting from these projects, but her day-to-day life did not allow her to dedicate herself to writing as she would like. Clara Amorim Duca, despite being a teacher and writing daily, had never imagined herself writing and publishing a book. Any Manuela Freitas has been working with cultural projects for some years now but found it difficult to move from a technical writing to a more literary one. Rose Miranda, on the other hand, spends at least two hours telling us a story in the smallest details, such as “he gave me 20 reais in two 10 bills” when talking about the moment she divorced from her husband and went after the children’s pension, but when it came to writing, she thought that she had to put written words like “meanwhile”, “in the face of what happened” etc. and cut her narrative so full of life.

As the books were part of a research process, my work as an editor of their writings over 10 months required the development of a writing methodology for each of these characteristics and routines. This process was also an experimentation in the way in which we can do ethnography by rethinking the production of reports and field data in a collective and not individualized way. Each author thus carried out their research, seeking and analyzing old photos, writing memoirs of their lives, interviewing relatives and close people, and collecting testimonials from members of the cultural and dance groups that composed their books. From this material transcribed and written by them, we read it collectively and reorganized the text into chapters. We built the path of each book in weekly meetings and by revising what they were producing, first the reports, after the text already worked on.

The movement to shift the reflection from co-authorship, thus, to that of editorial work as ethnographic departed from the recognition of the geopolitics of bodies in the production of academic (or literary) knowledge, as conceptualized by Ângela Figueiredo (2017), and from the positionality and experiences of those who are on the frontiers to build a “mestizo theory”, as Glória Anzáldua ([1981] 2000) does. This shift, however, also made us understand writing itself as a common

(Dardot; Laval, 2017; JÚNIOR et al., 2021), that is, storytelling as a community social technology that starts from the collective to occupy hegemonic places. But also a writing with the body and in the “pretuguês” [Black Portuguese] of so many people, theorized by Lélia Gonzalez (1983), and marked by a racial division of space that naturalizes the place of black people in favelas and flooded areas and the place of white people in city centers, on high and safe buildings (GONZALEZ, 1983), places where it is possible and desired to become a writer and academic knowledge producer.

With the collective production of these five books, therefore, it was possible to enhance agency in writing through a joint reflective experience, which makes the geopolitics of bodies visible and destabilizes naturalized places. Writing thus appears as a territory in dispute in which it is necessary to name oneself, so that “the racist does not give us a name”, as one of the authors of the project, Lucineide Souza, always states. Recôncavo da Bahia is a mostly black territory, where the knowledge related to afro-religions has resisted spiritually and epistemologically over the years (VALE, 2018). In this relationship between different ways of worshiping, we can see between the lines of an event that moves the city of São Félix, involving city hall, church, pilgrims and povo de santo. We also see the frictions that cross these power relations, arising from a colonial encounter:

so it all starts because there is a road. path of dust, pure land, shortcut through what maybe one day was all dense forest. then it was private property, pasture, the highway that crosses brazil from end to end along the coastline. an owner had, but they turned a blind eye, or rather better it would be. they made war and much blood. (BARBOSA, 2023, p. 21)

The reoccupation of an invaded territory, which gives rise to a quilombola becoming (BISPO, 2015), can also be a reforest, as Deisiane Barbosa (2023) writes in casamendoeira, regarding the construction of an adobe house on the rural area of Conceição da Feira. For Antonio Bispo (2015), the interlocution of oral languages with the written language of the colonizers is a practice of counter-colonization. Maria Aparecida Rodrigues (Dona Aparecida), a quilombola leadership, associates the struggle for the title of the land in Quilombo Grotão, Tocantins, Brazil, to the knowledge produced there: “But, it’s like saying: ‘we’re there’. We are resisting! Because we are the ones who are going to remark the territory. We’re not going to wait for the government to check in […]. First we have to riscar [scribble] and go where the risk of our knowledge passes. That’s the fight” (RODRIGUES, 2021, p. 25). And it is with the counter-colonizing practice that mixes oral languages with written language that we can riscar knowledge (RODRIGUES, 2021) of these authors and occupy academic spaces, even if their busy lives do not give them much time, “It’s like Conceição Evaristo says, right? Our life is always a story, each one writes the way they want” (MIRANDA, 2023, p. 57).

With Dona Aparecida, we also choose to “tell other stories” (HARAWAY, 2016) in search of indigenous, quilombolas, peasants, country people, more than human, science-fiction and others speculations that reveal ways of living that are simultaneously constituent and contradictory to the capitalist project, and that activate feminist imaginations of life, “near futures, possible futures and implausible but real presents” (HARAWAY, 2016, p. 136). It is also to produce ethnographic experiments by each engagement with the people with whom we build research and struggle (MORAWSKA, 2022). Writing, therefore, is a political act, as Any Manuela Freitas points out when she brings the daily life of two of hers great-great- grandmothers, her grandmother’s formation of Samba de Roda de Dona Dalva, her mother’s and her own:

Organizing a Samba de Roda group is a political act, so is writing about this practice transmitting methodologies. This book, a writing by many generations, also proposes a reflection on the obstacles present in the maintenance of cultural heritage and the challenges faced by Samba de Roda groups. Although we walk with a legacy coming from long steps, we are still far from solid recognition for our survival and preservation of cultural wisdom. (FREITAS, 2023, p. 14)

By following this proposal to activate the counter-colonial quilombola imagination from a black territory, the idea of these collective writings was to incite the appropriation of the hegemonic language of the written word by women from the Reconcavo of Bahia. It was also to produce narratives guided by a perspective that is generally silenced when it comes to the official history of the region. This writing also brought different written formats. Clara Amorim Duca (2023), for example, intertwined her own memories with the voice of the young people who were part of her dance company, CIA DUANA’S DE RITMO, formed in the early 2000s. Their narratives show the importance of this group for their growth and professional training. Duca (2023) also talks about the lack of funding for social projects in Cachoeira and how the group became a family, “composed of many people who had dreams” (DUCA, 2023, p. 129):

Culture and art do need support, investment, and encouragement, but as a structured government program, not as a favor from anyone. What impressed us was how it was possible to not value a group of young people dedicated to an artistic project that was already a success and recognized by the community. I didn’t want to commit my group to any kind of political exchange, whether from political parties or otherwise, and therefore we invested in our self-production and self-promotion. It was us and our art! (DUCA, 2023, p. 92-93)

The idea of keeping memory through the narratives of women storytellers guided the collective writing process in the Cachoeiras Project, when thinking of written books as inhabited, extended, expanded by the daily life of the Recôncavo da Bahia. This is how the books became the “Cachoeiras Collection”, launched in April 2023, by andarilha edições and financed by The Wenner-Gren Foundation: