Engaged Anthropology Grant: Suma Ikeuchi

In 2013 Suma Ikeuchi received a Dissertation Fieldwork Grant to aid research on “Brazilian Birth, Japanese Blood, and Transnational God: Identity and Resilience among Pentecostal Brazilians in Japan,” supervised by Dr. Chikako Ozawa-de Silva. Dr. Ikeuchi was able to return to the field in 2019 when she received an Engaged Anthropology Grant to aid engaged activities on “Jesus Loves Japan: Workshops on Migration, Religion, and Citizenship in Japan and Brazil”.

With the Engaged Anthropology Grant, I was able to travel to Japan and Brazil to share the results of my dissertation fieldwork conducted from 2013 to 2014. The yearlong fieldwork investigated why the Pentecostal Christian churches have flourished among the Japanese-Brazilian (i.e. Nikkei) migrant communities in Japan by probing the connections between their ethnic, national, and religious identities. State-sanctioned return migration is a growing phenomenon in Asia today, with major nations such as India and South Korea legally facilitating the “return” of foreign citizens descended from their emigrants. As part of this trend, Japan introduced a new type of visa in 1990 for foreigners of Japanese descent, which triggered the mass-migration of Nikkei Brazilians from Brazil. While Nikkeis benefit from the visa policy that confers the right to settlement virtually as a right of blood, they often feel discriminated in Japan for their ethnic ambiguity and working-class profile. In this context of racial tension and contested belonging, many have been converting to Pentecostal Christianity—a religion that has grown exponentially in Latin America since the 1970s and subsequently flourished among many Latino migrant communities across the globe. The fieldwork examined this transregional intersection of Asian return migration and Latin American Christianity.

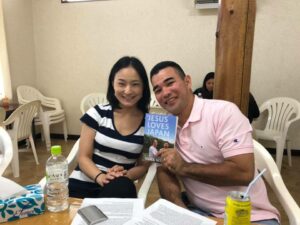

In July 2019, I returned to the main research site in Japan—a Pentecostal church in Toyota City attended by roughly 500 Brazilian migrants—to hold an informal workshop with the people who had participated in my study. The main purpose was to receive their feedback for the two main final products of the research. Since the completion of fieldwork in 2014, I have been able to edit a short ethnographic film In Leila’s Room (2016) and publish a book Jesus Loves Japan: Return Migration and Global Pentecostalism in a Brazilian Diaspora (2019 Stanford University Press). First, I screened In Leila’s Room to a group of core participants, including the main protagonist Leila, followed by Q&A. Some expressed a sense of amusement about the fact that the film incorporated what they considered to be banal interactions, such as family members speaking about barbecue. A vibrant conversation about observational cinema ensued.

Unlike the film, which is mostly in Portuguese, Jesus Loves Japan is in English, a language that the participants in the study cannot read. To make the book content accessible, I prepared a four-page summary in Portuguese and Japanese (many younger migrants prefer Japanese) and distributed it to the community members at the church on Sunday. In addition to the summary, they also received a fifteen-minute oral presentation in Portuguese from me about the significance of the study results and how their cooperation contributed to it. In total, I had roughly 250 people in attendance on this day, many of them previous participants in my study. “What do Americans think about us?” This was one of the most common questions, now that they have seen the book in English and heard about my representations of them in it. Although Toyota City has been a frequent destination for social scientists (both Japanese and Brazilian) who took interest in this migrant community over the years, some Brazilian residents there told me that they had never heard back from these scholars about what was done with the data afterward. As a result, many in the audience were excited to find out how the stories of their lives were recounted in the book, now circulating in an unfamiliar language. We continued our conversations in the church canteen even after the presentation was over. Many interviewees had the chance to see where in the book their remarks appear and listen to me explain how I incorporated them into my overarching argument about the relationship between migration and conversion. In these dialogues, the findings of greatest interest were about how the various church initiatives about “family restoration” seem to address the challenges that many migrant families face as they cope with distance, demanding work, and language barriers in a foreign land.

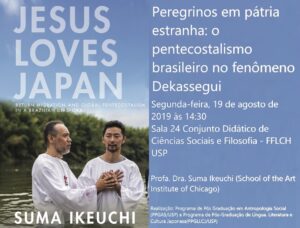

The grant also enabled me to organize workshops and deliver lectures about Jesus Loves Japan at five universities—one in Japan and four in Brazil—so that I could engage the scholars interested in the study results in their respective languages. I participated in a workshop about my book in Japanese at the Nanzan Institute of Religion and Culture in Nagoya in June 2019. The talk was followed by the comments by two Japanese scholars and Q&A. Since one potential shortcoming of the book is that the majority of references cited are in the English language, their sharp feedback informed by the sources in Japanese constituted valuable and much-needed inputs. In August 2019, I traveled to Brazil to speak at The University of São Paulo, The Federal University of São Paulo in Guarulhos, The Federal University of São Carlos, and The University of Brasília. This time I delivered the lectures in Portuguese, followed by Q&A in a mixture of Portuguese and English. The audience consisted of Brazilian scholars and students, many of whom were deeply interested in the global expansion of Brazilian Pentecostalism due to the growing political power associated with the religion with the recent election of President Jair Bolsonaro. The comments and questions I received from the scholars based in Brazil were very different from those from the researchers in Japan, probably because of the diverging social positions of Protestant Christianity in the two respective societies. For example, some interlocutors inquired if the migrant churches I studied sought any political power in the mainstream society. I responded that doing so is more difficult in a non-Christian society such as Japan, especially for a foreign migrant minority such as Nikkei Brazilians. Overall, the feedback I received in Japan and Brazil demonstrate that different scholarly communities can bring to the table different analytical strengths informed by their respective intellectual and political backgrounds. The bilingual lectures in the two countries reaffirmed the importance of intellectual exchange across linguistic and national boundaries, and I am grateful for the Foundation for enabling me to advance such an initiative.