Engaged Anthropology Grant: Maria Theresia Starzmann

Maria Theresia Starzmann is Assistant Professor of Anthropology at McGill University. She originally was awarded the Dissertation Fieldwork Grant in 2008 as a Ph.D. student at the State University of New York – Binghamton, to aid research on ‘Embodied Knowledge and Community Practice: Stone Tool Production at Fıstıklı Höyük,’ supervised by Dr. Reinhard W. Bernbeck. After analyzing the technological organization of stone tool production at this 6th millennium BCE site in southeastern Turkey, Dr. Starzmann applied for and was granted the Engaged Anthropology Grant in 2013 to develop and present a series of workshops for schoolchildren living in proximity to the research site. In this post, Starzmann shares her experiences educating young people about Neolithic lifeways.

Seen from the present, the ancient world often appears foreign to us. Looking at a Late Neolithic site, the contemporary reader may expect to find functionally differentiated stone tools—an archaeological ‘tool kit’ similar to the implements in a North American kitchen drawer. The absence of such artifacts often comes as surprise: as my research at the site of Fıstıklı Höyük in Southeastern Turkey has shown, Late Neolithic villagers lived with a relative paucity of material items. Up until the late 20th century, this scarcity has led archaeologists to describe the Late Neolithic societies of the Middle East as ‘primitive.’

Against such an ‘othering’ of past social groups, my dissertation research set out from the understanding that the past is more than an impoverished mirror image of the present. Seeking to share my alternative reading of the Late Neolithic past, I applied for a Wenner-Gren Engaged Anthropology grant. The idea was to offer a series of workshops for school children in Turkey, providing local students with an opportunity to explore the ancient world in their own terms. In developing the workshop materials, I believed it particularly important to counter a reading of ancient cultures as ‘primitive.’ The scarcity of artifacts documented at Fıstıklı Höyük, for example, is better understood as the basis for sharing things than as indicative of a primitive lifestyle. Against this background, Late Neolithic communities appear in a different light: while they may have lacked a relatively hierarchical social organization, group cohesion seems to have been established by collective work in the context of ‘communities of practice.’

With these ideas in mind, I returned to Şanlıurfa, where I had carried out my dissertation fieldwork. Two colleagues, both of who had previous experience working in educational projects, accompanied me. Nilgün Çakan, a social anthropologist from Berlin, Germany, and Mina Eroğlu, an archaeologist from Ankara, Turkey, were engaged project partners and precious travel companions throughout our stay in Turkey.

Together, we visited a local elementary and middle school, Özel Şanlıurfa Saraç İlgi Okulları, for the duration of two weeks, where we conducted several workshops with 10-12 year old students. Prof. Evangelia Pişkin of Middle Eastern Technical University (METÜ), who kindly agreed to take on an advisory role in the project as well as establish the contact to the local school, supported the preliminary organization of the workshops. At the school, Mr. Halil Sarac and Mr. Mehmet Tokgöz were attentive and helpful in coordinating the workshops and providing the necessary technical equipment.

In organizing the project, it was crucial that the workshops were interactive. This meant that we provided the space for children to respond to questions and prompts as well as to as ask their own questions. Each workshop was conducted as a conversation with the children. In an instructional session, we first explained some of the basics of archaeological work. Starting from how to acquire an excavation permit to the actual excavation process, we also introduced the students to the documentation, analysis, and curation of artifacts. We had brought with us a small study collection of archaeological artifacts—pottery sherds and stone tools—that the students analyzed.

Based on the archaeological materials, the students were quick to draw comparisons between ancient cultures and contemporary village life in Turkey. Many students told us about traditional cooking and building methods not only to be found in archaeological textbooks but also in rural areas in Turkey: they mentioned the use of the tandır oven for baking bread, or of mud-brick for the construction of the beehive-shaped houses that can be found in the area of Harran, just 20 km south of Şanlıurfa. There was also distinct sense among the children that the past was in many ways different from the present and characterized in particular by the lack of modern technologies. This lack was not perceived in a negative way, however; rather, as one student put it, “People back then were more intelligent, because they didn’t have TV.”

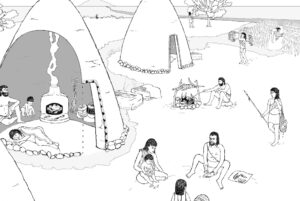

The workshop also included an in-class exercise: inviting the children to travel back in time, we asked them to imagine a typical day in the Late Neolithic village of Fıstıklı Höyük. What would a day in the life of a 11-year old boy or girl have been like at Fıstıklı Höyük? In which ways was past life different from your life today, and in which ways would it have been similar? In answering these questions, the children relied on reconstruction drawings of Fıstıklı Höyük that Toronto-based artist Bryan DePuy had contributed to the project. The images depict Late Neolithic village life—men, women, and children are busy fishing, cooking, and making pottery or stone tools—and they also give a hint about the nature of past social relations.

In their stories, many children actively engaged the idea of a ‘sharing economy,’ with one student stating that “life back then was better, today people are egoists.” This sentiment corresponded to a general understanding among the children that in Late Neolithic societies there might have been more room to accommodate people who “had different talents.” That these talents needed to be passed on between the generations was also of concern to the students: in the reconstruction drawing of Fıstıklı Höyük we see adults sitting with children, leading several students to suggest that “knowledge was shared between father and son.” But according to the students, the status of parents or village elders was not established by way of coercion. Instead, “older people had more authority, because they were more experienced,” and someone who stood at the top of the social hierarchy of the village, maybe a ‘sheikh,’ was “not someone powerful, but someone smart.”

To Mina, Nilgün, and myself, these answers demonstrated that our project was about much more than teaching children about cultural heritage. Initially conceived of as a way of bringing ‘home’ my dissertation work, the workshops soon unfolded into a genuine conversation in which the students shared their ideas about a different world. The children’s stories are beautiful accounts of the possibilities of a world that is inclusive of diversity, communal ways of living, and sharing. The project thus opened up new spaces for talking about history and for learning from each other. Or, as student Doğa put it in her story about living a day in a Late Neolithic village, “I am sure, I could teach [the people from the past] a few things and most likely they would be able to teach me a few things as well.”

As per her request, we have included Starzmann’s summary of her project in Turkish.

Türkçe özet:

Şanlıurfa-Türkiye’de bulunan bir ilköğretim okulunda organize ettiğimiz bir seri atölye çalışmasının hedefi, bölgenin Geç Neolitik dönemi ile ilgili bildiklerimizi öğrencilerle etkileşimli bir şekilde paylaşabilmekti. Arkeologların ne iş yaptıkları ile ilgili basit açıklamalar içeren bir sunumdan ve küçük bir etüdlük eser kolleksiyonunun çocuklarla birlikte analiz edilmesinin ardından çocukları, bir Geç Neolitik köyü olan Fıstıklı Höyük’te gündelik hayatı keşfetmeye ve geçmişe dair kendi yorumlarını ortaya koymaya teşvik ettik. Çocuklarla yaptığımız konuşmalar sırasında eski dünya ve kadim hayatlar rengarenk bir şekilde yeniden hayat buldu. Bunun da ötesinde, çocukların “sorunlu” bazı arkeolojik buluntular üzerine yaptıkları yorumlar, halihazırdaki arkeolojik modellere yeni bakış açıları getirdi: örneğin, arkeologların genelde karmaşık toplumsal organizasyonun yokluğuyla tanımlamaya meyilli olduğu Geç Neolitik dönem toplulukları konusunda çocuklar, “paylaşım ekonomisi” ve komünal yaşam ile karakterize olmuş bir kültür olasılığı üzerinde durmayı tercih ettiler.