Engaged Anthropology Grant: Hilary Faxon

From 2017 to 2019, I conducted an ethnography of agrarian and political change in rural Myanmar. In 2022, I worked with Salai Suanpi to illustrate my findings in the Myanmar style of satirical cartoons. The Wenner-Gren Foundation generously supported both projects. The book I am writing now—in the wake of a 2021 military coup and the violence that is still unfolding—focuses on grassroots struggles for land during a decade of quasi-democracy.

Land was central to post-authoritarian promises of democracy and development in Myanmar during the 2010s. Yet it was also critical to longer histories of surviving the state: the everyday practices through which contemporary smallholders secure material and political survival over successive periods of coercion, abandonment and violence.

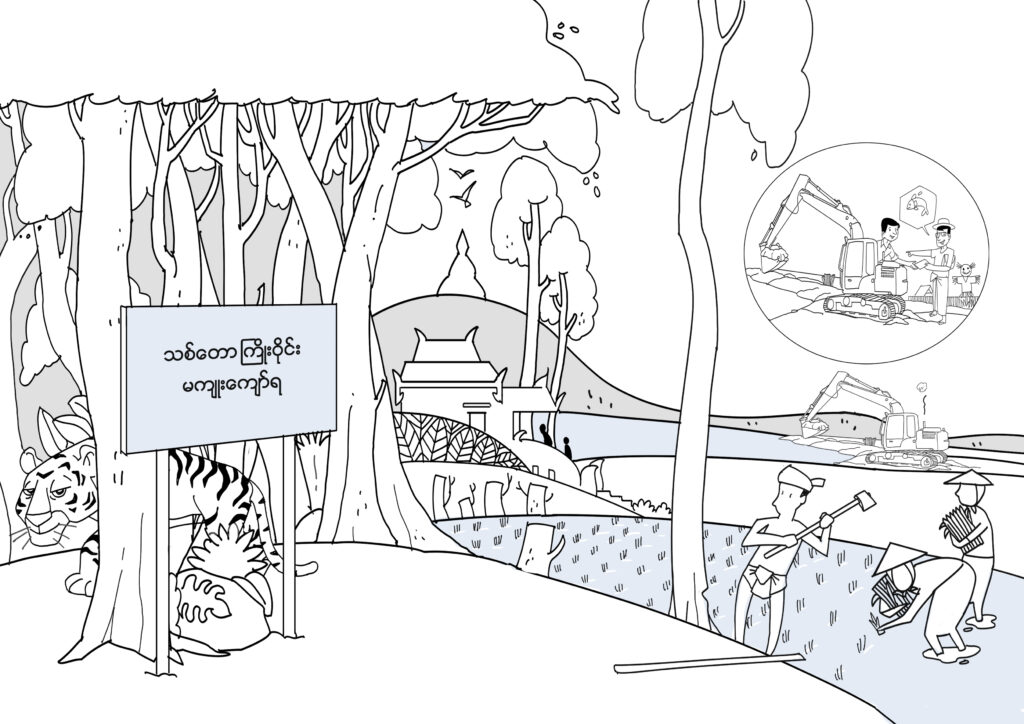

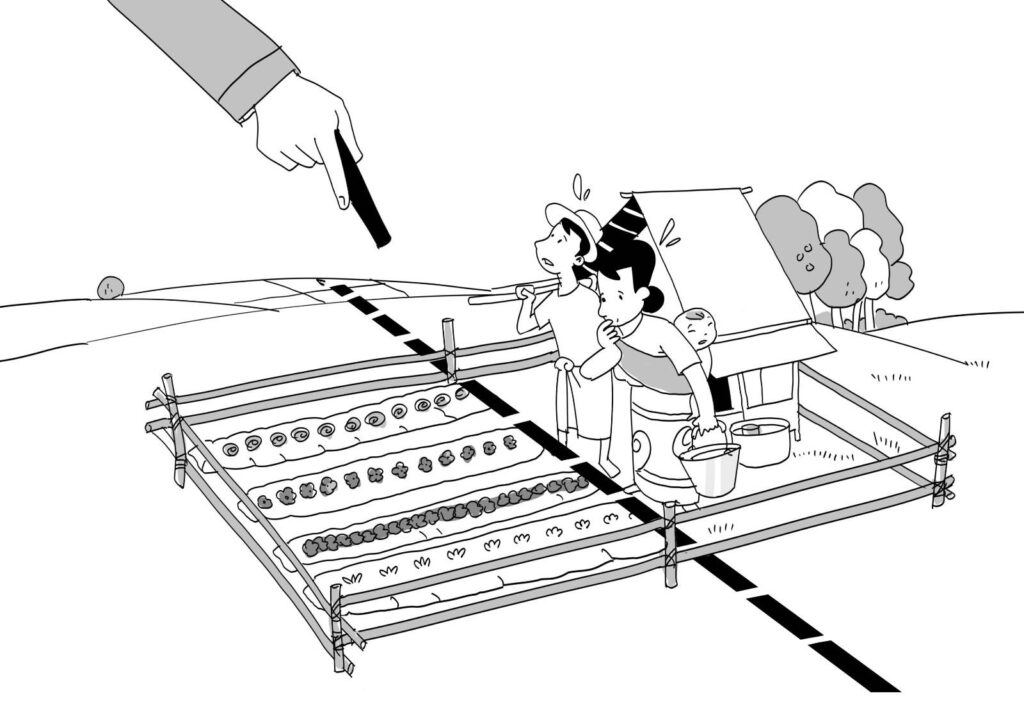

The hard work of securing livelihoods under successive regimes of state violence and neglect shaped landscapes like this one—zoned as forest reserves during the colonial period, cleared for smallholder cultivation during socialism, and then partially converted to fishponds using capital sent back as remittances.

Land is not only key to making a living, but also to the gendered practices of care and connection that I call making meaningful life. Just as labor to secure subsistence shapes the landscape, these place-based practices create and sustain family and community, reproducing agrarian society.

This embodied history and ongoing reality shaped efforts at land reform during the attempted political transition in the 2010s. While elites held up land rights as a key milestone on the path towards democracy, for farmers, new rights were inseparable from new forms of risk.

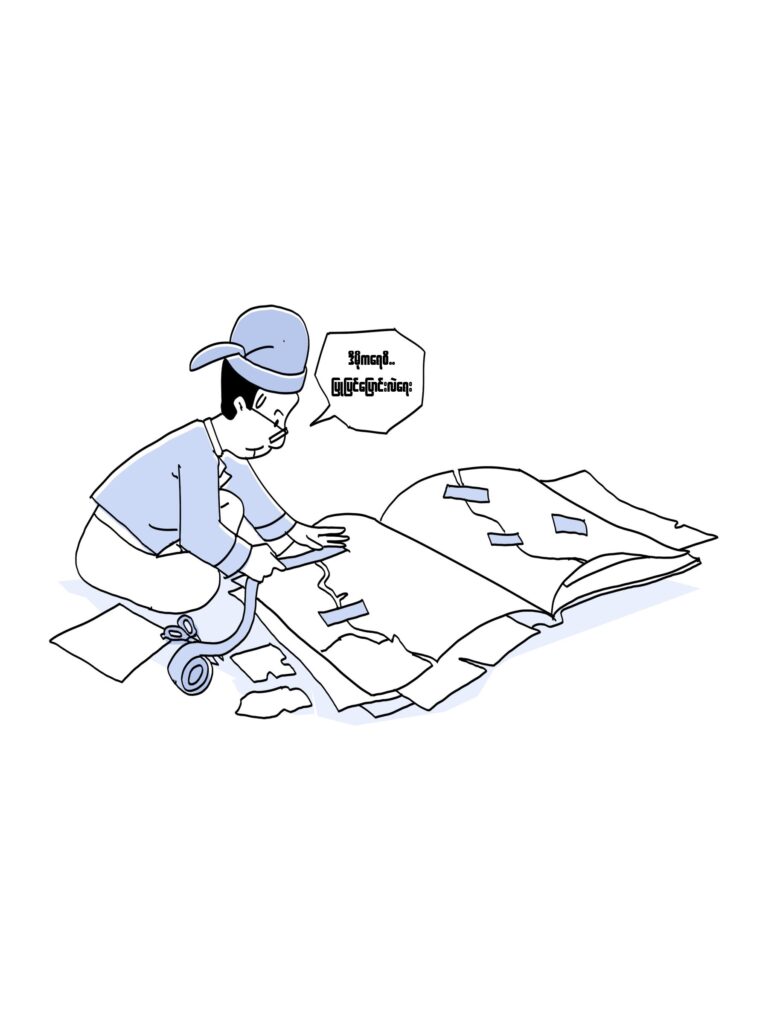

New policies did not erase colonial, socialist and authoritarian regimes of land control. Rather, new laws were littered with legal debris: conflicting ideas of land governance, value and ownership inherited from past regimes that linger on in contemporary text.

In practice, the work of land reform was one of pasting together old rules, as captured by this image of a traditionally dressed bureaucrat with sweat on his brow, taping together the law and pronouncing in ‘democratic reform.’

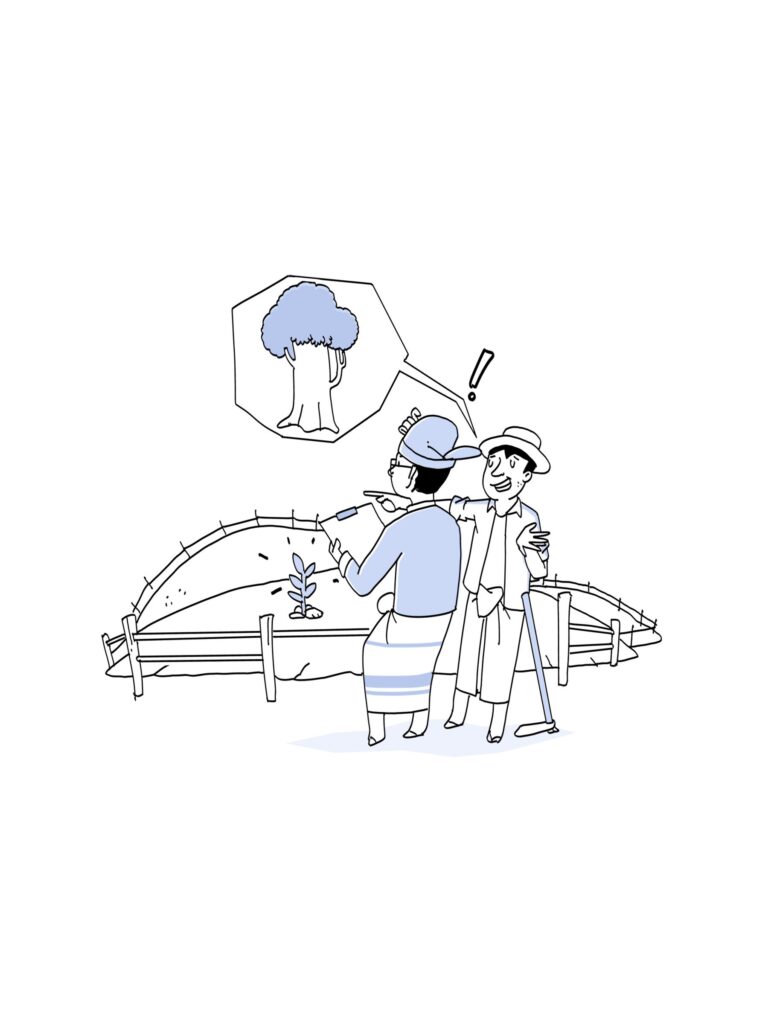

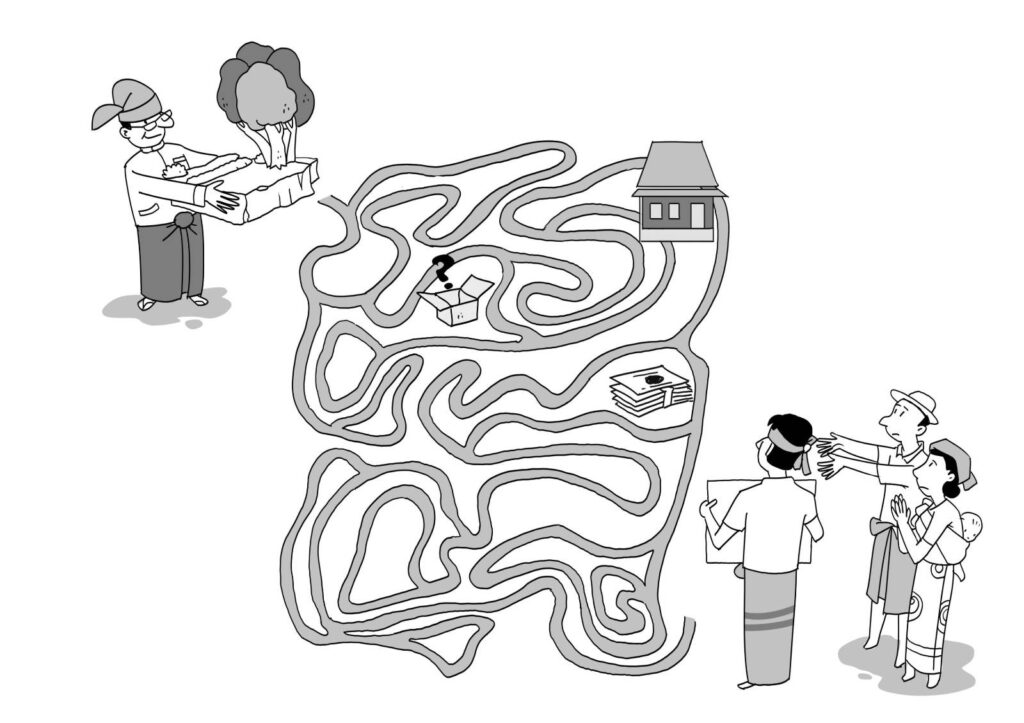

But farmers were not only passive victims. They leveraged the law to make new sorts of claims, stretching acreage and shifting land use categories to optimize and mitigate. In so doing, they negotiated risky rights in ways that built on the longstanding practices of surviving the state.

Efforts to give land back and recognize ethnic territory raised similar challenges for smallholders. Conflicts between claimants erupted when land grabbed by the military was returned, prompting performances of democratic deservingness. Farmers cultivating land that crossed provincial boundaries struggled when ethnic elites demanded restoration of the colonial borderline.

These episodes evidence specific structural failures in the 2010’s democratic project. More broadly, smallholders’ experiences emphasize continuity, as generations draw on land for production and social reproduction, amidst intermittent state violence and neglect. Their stories suggest that reimagining land after the revolution demands a paradigm shift: from surviving the state, to seeking justice.