Engaged Anthropology Grant: Alex Blanchette and ““Factory Hog Farming, Capitalist Natures, and the New Rural American Frontier”

Alex Blanchette is Assistant Professor of Anthropology and Environmental Studies at Tufts University. In 2009, while a doctoral candidate at the University of Chicago, he received a Dissertation Fieldwork Grant from the Wenner-Gren Foundation for research on “Factory Hog Farming, Capitalist Natures, and the New Rural American Frontier”, supervised by Dr. Joseph Masco. This Engaged Anthropology Grant project developed from Blanchette’s dissertation workplace research on the interspecies nature of industrial life in the American “factory” farm.

Since 2008, I have been conducting workplace research on the nature of industrial life in a 100-mile radius zone of the U.S. Great Plains, one that is made and remade every day to unlock new value in the hog’s body and mind. After becoming the center of operations for some of the world’s largest pork corporations some two decades ago, this region now annually manufactures almost 7,000,000 pigs across all stages of being from pre-life in breeding to post-death as 1,100 distinct product codes. Within the factory farm’s workplaces, the process is not so simple as merely raising and killing “the pig” as a singular organism. Instead, these operations are premised on developing global sales networks, machines, divisions of labor, statistical standardization, ideologies of life, and embodied craft practices to (re-)industrialize the meat, fat, skin, organs, bones, blood, feces, viruses, reproduction, growth, diets, behaviors, instincts, and sentience of the porcine species. Such a capital-intensive intervention into the fissures of animal life and death has drawn thousands of new residents and created a vibrant – though fragile and unequal – cosmopolitan rural community where 26 languages are spoken in the primary school. Reminiscent of a 19th century company town – yet one that is spread over a wide geographical, political, and ecological expanse – it is a place whereby the vast majority of livelihoods have become socially and economically dependent on the industrial pig. If it wasn’t for the pigs, as some residents liked to ambiguously remind me, “this place would be a ghost town”.

In its dominant mythos, the factory farm is supposed to be a space of total confinement. Industrial agriculture’s dreamworld is one where porcine life is hermetically sealed inside networks of biosecure barns hidden in grain fields, backwater trucking routes, and invisible slaughterhouses. Over several years of ethnographic research, however, residents across social classes helped me sense a region where the massive scale of hog life saturates social experience – a place where struggles for justice, cultural politics, and social practice at times congeal on terrains of animality and its traces. Subtle shifts in town odors indexed a different stage of hog life or death, jarring forth memories of past labor. Former opponents of the factory farm wrestled with the fact that they often sell their crops to the corporation to sustain their livelihoods. Records of the slaughterhouse’s work regime and its repetition were sometimes etched onto workers’ bodies. Employees recounted, with great pride of craft and care, how raising pigs made them re-interpret and value their own human domestic lives (and vice versa). Hog diseases were invisibly omnipresent across the landscape, as people were forced to monitor their habits and sociality outside of work to ensure that illnesses would not transfer across their bodies, and lead to new infections in untainted barns of swine. It seemed that workers or managers could always share their own means of sensing the industrial hog in public space – signs that indexed a subtle reading of the mass-production of life, ranging from its totalizing potential to its tenuous margins of return. Rather than being purely confined in barns, the hog could re-orient everyday social perception whether artificially inseminating sows, manufacturing soup base from bones, or sitting on the couch at home.

The book project that emerges from this dissertation centers on the notion of the “factory” in the factory farm, the politics of lively standardization, and workplace relations underlying the making of the modern pig. However, in the summer of 2013, with support from the Engaged Anthropology Grant, I was able to return to this research site with a photographer to begin production on a series of exhibits developed with reference to residents’ diverse insights into the region’s broader public sensoria. Initial engagements were varied, premised on both learning new ways to depict the region and contributing to ongoing community projects. I conducted discussions of the dissertation’s findings with key informants – especially those who are not from English-speaking backgrounds – eliciting commentary, support, and critique for future iterations. At the same time, many older friends whose ideas and practices animate parts of the dissertation have since moved on to other places. This certainly complicated some planned forms of dialogue and engagement, but it allowed us to contribute to new community efforts that had emerged since 2010. For example, this included writing newspaper biographies and photographs for a festival organized by migrants originally from South Sudan and Ethiopia who had settled in the area. These conversations also served to inform initial approaches to the visual subject matter, whether they depict a boar stud, growing farm, truck wash, a public gathering space, or a living room.

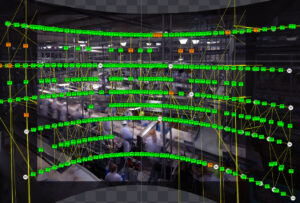

In opposition to both the exposé and the PR image, whereby the camera is marshaled to transparently capture the essence of the factory farm, the goal of this visual project was to intensify the multiple ways of sensing scenes of concentrated human and animal life. While any photograph is both real and constructed, this project embraced the medium’s indeterminacy in order to highlight the cultural politics that are present within the factory farm (and not just launched against it from outside). To differing degrees at each site, managers selected and prepared scenes prior to our visit, making the images partial records of an ideal aesthetic. Workers often posed in modes of embodied intimacy and craft knowledge that industrialization relies upon, and that standardization can never fully eradicate. My photographic collaborator refined a technique that enabled him to adjust and construct minor details of images. Facing each setting for over an hour at a time, he took up to 1,400 photographs of sections of a site – say, from a slaughterhouse’s catwalk – in a way that enables him to later digitally stitch together large-scale and incredibly detailed images (see second and third images), while subtly adjusting the time, tenor, scene, and subject of the interspecies interactions depicted (for example, in terms of a person’s bodily positioning or a knife movement). Indeed, the resulting images can be viewed as drafts subject to an ongoing editing process. We plan to initially exhibit images in this host community (and perhaps others like it) to both build conversations around the broader research through public talks, and to elicit commentaries from employees and residents across social classes and local communities on the depicted scenes and their representation. As part of an ongoing engagement project, these interpretations, commentaries, and reflections would then become central parts of the overarching presentation of future public installations or exhibits in urban locales around the industrialization of human and animal life.