Engaged Anthropology Grant: Brendan Tuttle

Brendan Tuttle is an Adjunct Associate Professor at Brooklyn College. In 2009 he received a Dissertation Fieldwork Grant to aid research on “Lives Apart: Diasporan Return, Youth, and Intergenerational Transformation in South Sudan,” supervised by Dr. Jessica R. Winegar. In 2014 Dr. Tuttle received an Engaged Anthropology Grant to aid engaged activities on “New Histories for a New South Sudan: A Public Anthropology Project”.

For my Engaged Anthropology project I planned to return to my fieldwork site near Bor Town, the capital of Jonglei State, in what is today South Sudan. When I was first there in 2009 and 2010, the town was a settlement of roughly forty thousand people. Many had recently arrived after the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) in 2005, which formally ended Sudan’s long-running civil war. My dissertation research examined the processes by which people in Bor were reconstructing their lives and trying to get by in difficult circumstances, making choices about where to settle, fashioning binding agreements with one another, and looking for humor in their predicaments. Many people I spoke to emphasized the importance of ordinary routines and life trajectories. During Sudan’s second civil war (1983-2005) this show of resilience in the face of disaster (riääk) was framed in Bor as a resistance strategy called gum ëlik (‘quiet suffering’ or steadfastness). By attending to how people caught by violence pursued projects that extended beyond it, I sought to counter ideas of Dinka society as particularly prone to violence—an idea that has often served to elide the role of governments, petroleum companies, international NGOs and financial institutions in the insecurity and instability of the county by attributing violence to local cultural forces.

The outbreak of civil war in December 2013 prevented my return to Bor. Hostilities began in Juba, the capital of South Sudan, and followed the fault lines of unresolved political divisions within the country’s governing party, the SPLM, and the army, the SPLA. (Many journalists have evoked ‘tribalism’ and ‘deep ethnic divisions’ to explain this war. It should be underlined that ethnicity was not the cause of South Sudan’s conflicts. It was the outcome.) During the following months, Bor and other state capitals in South Sudan changed hands several times in battles fought between government forces and the Ugandan army, on one side, and defected soldiers and armed irregulars, on the other. By the end of January, 2014, the destruction of Bor Town’s market center was virtually total. The town was deserted except for the soldiers stationed there to occupy it.

All of the surviving participants in my dissertation research had evacuated Bor Town and the surrounding countryside by the end of December 2013. Many relocated across the Nile to a large IDP site in Minkaman (Guol Yar). Others had travelled south to Juba, and a few joined relatives in Kenya and Uganda; still others relocated farther afield. In January, I stayed with my former research assistant in a home rented by his uncle on the eastern fringe of Nairobi, and he stayed with me in Juba before departing for South Dakota. In February, I travelled to Minkaman. Though I facilitated two workshops in Juba, much of my engagement work consisted of traveling around South Sudan and Kenya and talking with people wherever they were able to meet. Many discussions were held in my house in Juba. I met others singly and in groups in their homes, at coffee stands, or in hotels located in the growing informal settlements that ring Juba. I would generally begin by presenting my dissertation findings and reviewing and revising written portions of the work with participants and then let the discussion develop any way participants wanted.

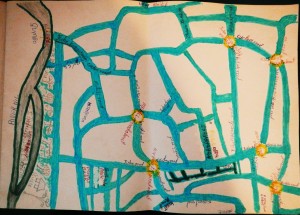

My interlocutors challenged portrayals of IDP camps and informal settlements as ‘non-places’, and guided my attention toward the many locations where their lives unfolded. A group of people who had once shared a geographic place, but no longer do, is a common mode of ‘community’ in contemporary South Sudan. Many of the people I knew best in Bor had been born nearby—where they were bound together by overlapping ties of kindship, marriage, partnership, and friendship—and displaced in the 1980s to varying degrees of geographic and social distance. Others had come to know each other in refugee camps in Uganda and Kenya and resettled together in Bor after 2005. Participants in the project drew maps and described the histories of the places where they had lived and the relationships that they had formed there. These discussions provided a lesson about how the customary anthropological practice of studying in one locale tends to privilege genealogical modes of belonging (particularly in South Sudan) by failing to capture patterns of movement and plural association, the ways in which people live out their lives across multiple places and social fields.

The accounts people told about their experiences of migration destabilized depictions of refugees and IDPs as people whose movement is without history, politics, or self-reflection. People spoke about the hardships of building homes with improvised materials and of raising families without adequate food, clean water, or access to schools. Many described their struggles to be generous to others: to host visitors, foster children, and support friends and in-laws. Efforts to live normal lives in these circumstances were partly by way of simply trying to get by. But the maintenance of ordinary routines, standards of generosity, and lifecycle processes also embodied a refusal to be reduced to an existence totally determined by violence. In Minkaman, friends told me how difficult it had been to leave their homes unguarded and risk accusations of cowardice by leaving conflict zones (or demanding that family members do so). One man compared the mounting numbers of IDPs and refugees published each week by the UN to an election return: “They’re defecting! The people are voting against this war with their feet.”

The Engaged Anthropology project allowed me to maintain contacts and share my research. It also led to new collaborations. A major goal of this project was to collect and write local histories in order to provide alternative representations of people who are often portrayed as being unable to reflect on their own lives and situations. One particularly productive collaboration has been with Paul Ruot Kor Wan. I am currently editing for publication selections drawn from his manuscript, titled “The Myth of Kiir Kaker,” which is based on oral testimonies that he collected during his stay in UN POCs (‘Protection of Civilian’) sites in Malakal and Juba. Paul Ruot helped me to organize two workshops in Juba in which I presented my research and facilitated discussions of oral history and ethnographic methods. One participant, who had collected histories that he hoped to publish, recalled his feeling of despair when he returned to Bor to see what of his possessions were salvageable and found his home ransacked and his research and books torn and scattered. The Engaged Anthropology Grant enabled me to provide electronic copies of books and articles about East Africa, South Sudan, and Sudan on a USB-stick to people who were cut off from these materials by publishers’ paywalls, the cost of academic publications, and the inaccessibility of libraries and postal systems.

Overall, my Engaged Anthropology grant provided me with the resources to reconfirm connections and develop new engagements. I am grateful to the Wenner-Gren Foundation and, especially, all the participants who took the time to attend workshops and to speak with me.