Engaged Anthropology Grant: Serious Play: Anthropology and Game Design for Farmworker Health and Justice

Eight students from California’s Pájaro Valley and two interns joined anthropologist Dvera Saxton in summer 2015 in a creative workshop that led to the conceptualization and design of two farmworker-themed video games. By winter 2016, the games will be digitized and ready for their public debut on the Internet. The students, who all come from farmworker families, learned ideas and methods of anthropology, game design, and graphic design and combined those new insights with their own life experiences to create the games. It is our hope that our video games will foster greater empathy for farmworkers and a deeper sense of appreciation for the skilled but socially and economically undervalued work that they do in the strawberry fields.

When you play classic board games like The Game of Life or Monopoly, the stories and narratives, and even the outcomes of game play, do not necessarily reflect our lived realities. And the values that the contemporary versions of these games instill are also problematic, and deviate from those intended by their originators (and, according to historian Jill Lepore, author of The Mansion of Happiness: A History of Life and Death, certainly from those of the Old World inventors of the some of the first spiral board games in India, East Asia, and the ancient Middle East).

Immigrant workers, are largely invisible in contemporary popular board and video games (as they are in real life), despite their critical roles in producing and maintaining wealth: the construction workers who build dream homes, the housekeepers and nannies who maintain the gleaming interiors and care for the children of more privileged full time workers, the gardeners who preen and prune the landscaping, and the farmworkers who harvest the strawberries plunked into the champagne or sliced atop a Starbucks parfait.

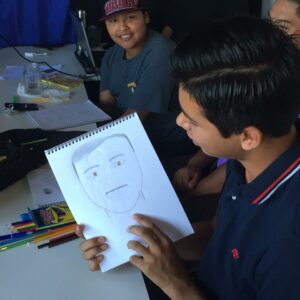

Even amidst great struggles—from dangerous border crossings and family separations to devastating and permanently disabling injuries—farmworkers and their families still found time for humor and playfulness in everyday life. It is from my observations of farmworker families at work and at play that I drew much of the inspiration for the Game Over: Game Design for Farmworker Health workshop. With the collaboration of two interns–Kevin Cameron, a UC Santa Cruz Game Design program graduate, and Juan Morales Rocha a UC Santa Cruz Cognitive Science major and son of farmworker parents–eight students (recruited from Watsonville High School and Pájaro Valley High School), and our host, the Digital Nest (a non-profit that provides space for youth and adults to learn about emerging technologies and collaborate on projects), we developed two farmworker themed video games that we hope will foster more empathy for the people who harvest the fresh foods we eat.

I went back to my field notes to think about the instances of playfulness I observed in farmworkers’ everyday lives, and how this contrasted with the unbearable struggles and suffering they endured behind the scenes. Play is a method of coping with seemingly insurmountable challenges. It is a survival strategy, a way of blowing off steam or decompressing from a long day at work, and also a means to instill values and morals in children and to reinforce them amongst adults. As anthropologist James C. Scott observed, there is a playfulness to rural workers’ resistance in the fields.

Farmworker play is diverse, and takes place both at work and off the clock. El Teatro Campesino toured across California’s farm fields, entertaining workers and inciting them to respond to injustices through comedy and theatrical plays. At work, farmworkers may sing along with the radio, sneak a ripe berry into their mouths, or take part in lunchtime soccer matches or gambling card games. At one field site site near a flower nursery, I saw that farmworkers had ingeniously made their own impromptu glove drying rack. At farmworker households, families played rounds of loteria (a classic Mexican version that is similar to bingo), especially at Christmas time. I reminisced about the guerilla piñata parties an area activist group would throw for farmworker neighborhoods around Watsonville at Christmas time. At a community garden run by farmworkers, children played by running up and down the rows and occasionally helped their parents. All the while, they were learning the differences between edible and inedible weeds and how to grow food for their families the same ways they do back home in Mexico. I thought about the participation of farmworkers and their children at rallies, and the clever and colorful posters they made. How could we mobilize this playfulness to challenge popular misconceptions about farm work and farmworkers? What games could we create that might help farmworkers preserve their health, or know their rights?

California’s Pájaro and Salinas Valleys are major strawberry-growing regions, producing 80 percent of the strawberries consumed throughout the United States. In this region, from May through October, thousands immigrant laborers, mostly of Mexican and Central American descent, rise before dawn to harvest strawberries, red and black raspberries, and blueberries. Many people enjoy these and other fruits at breakfast time, several hours after the sun comes up.

These strawberry fields (not the ones idealized by the Beatles) are where I conducted my dissertation research on farmworker health and wellbeing. I observed that many factors—from pesticides to the piece rate of pay—contribute to devastating farmworker health problems that layer and evolve over time in bodies and communities. My research and activism in response to farmworker health issues involved networks up and down the agricultural hierarchy. It has and continues to contribute ethnographic labor and critical analysis and reflection to social and environmental justice movements.

During our workshop, we merged the methods and concepts of ethnography, game design, and graphic design to make a series of serious games. This kind of game play aims to achieve more than entertainment. There is a great range of serious games, and the ideas and ethics they promote: from social justice causes to ethically problematic military and police training games. In addition to fostering empathy for farmworkers, we want our games to serve as educational and political resources in response to the a-political curriculum games featured on the websites of agribusiness companies and advocacy organizations, such as the American Farm Bureau and the California Strawberry Commission.

We conducted participant observation by playing and discussing many different board and video games with farming, food, immigration, and political themes. Some featured explicit and serious social justice themes, like The Migrant Trail. In this game, players can take on the role of an immigrant crossing the U.S.-Mexico border, or the role of a border patrol agent. We thought critically about the problematic storylines of games like Harvest Moon, which features a young farmer who can till, tend, and harvest the land without ever running out of stamina. This is a stark contrast to the experiences of farmworkers, who are often permanently disabled by the repetitive motions and intense pace of the labor.

Each of these games are fun to play, but for these teens, playing The Migrant Trail proved to be a more powerful experience than Oregon Trail, because their families’ stories are brought to the center of the gaming experience. So too, are the tensions between first generation immigrants and their descendants, some of whom, the youth observed, ironically, get jobs as border patrol agents. Playing a border patrol checkpoint agent in the game Papers, Please! gave students temporary access to indiscriminate amounts of power over the lives of other migrants trying to get into the fictional country of Arstotzka. The longer they played, the less sympathetic they became to immigrants’ pleas and stories, and the more obedient they became at enforcing the bureaucracy.

There are opportunities for anthropology, with the creative assistance of communities and other disciplines, to flip the script on games and other modes of learning and play in ways that aim to validate and politicize everyday life. The games that we came up with this summer provide a constructive means of engaging some of the complex and serious issues that farmworker families face every day. We will be throwing our game launch party in Winter of 2016, and we look forward to sharing our work with Pájaro Valley farmworker families, teachers, health care providers, non-profit directors and staffers, and elected officials, and from there, the rest of the internet accessible world. We hope that the games inspire other kinds of pragmatic, or practical, solidarity with farmworkers, in addition to furthering the trend of disseminating anthropological research by unconventional and innovative means.

After analyzing and playing these and other games, and brainstorming different ideas and variables for our own farmworker-themed game, we developed, constructed, play-tested, and refined two video game prototypes. Our game suite, Guardians of the Field: The Strawberry Jam (or Guardianes/as del Campo: El Jale de la Fresa in Spanish) will be launched online with free access in Winter 2016. One of the games simulates the experience of working at a piece rate of pay and the work of picking and grading berries for different global markets at a fast pace. The second is puzzle in which the player must pick and arrange the berries into a series of baskets under a time limit. In the end, the berries in each basket must weigh approximately one pound and must not overflow. Both of these are highly skilled parts of strawberry farm work. Our teen coconspirators know, sometimes from second hand knowledge from their parents and grandparents, and sometimes from first hand knowledge having spent summers alongside their kin in the berry fields, that farm work is not merely mindless physical labor. In reality, a lot of skill, focus, knowledge, and care, as well as physical energy, goes into picking and packing the strawberries that end up on supermarket shelves and in our refrigerators.