Engaged Anthropology Grant: Jacob Sauer

While a doctoral student at Vanderbilt University, Jacob Sauer received a Dissertation Fieldwork Grant in 2008 to aid research on ‘The Creation of Araucanian Anti-Colonial Identity During the Contact Period, AD 1552-1602,’ supervised by Dr. Thomas Dalton Dillehay. In 2013, he received the Engaged Anthropology Grant to aid engaged activities on ‘Presenting the Archaeological Past to Mapuche Communities and the Public in South-Central Chile,’ 2014, Chile.

It was fortuitous that my presentations in Chile to fulfill the Engaged Anthropology Grant took longer than I expected to carry out (I blame my daughter being born), as it happened to coincide with the month celebrating the country’s cultural patrimony. My Wenner-Gren funded research was carried out in the area of Pucón-Villarrica in southern Chile, along the western flanks of the Andes Mountains. I excavated a site known as Santa Sylvia, which had four different occupations, dating to AD 900, 1100, 1585, and 1850. The 1585 occupation included a Spanish “fortified house” that had been previously excavated by Chilean archaeologist Américo Gordon, who focused on the Spanish occupation of the site. My aim was to examine any previous occupations of the area by the Mapuche culture, to see what sort of changes came about in that culture before, during, and after the Spanish arrival.

The Mapuche are Chile’s largest Native American culture with a population of nearly 2 million living primarily in the capital city of Santiago and in an area traditionally known as the Araucanía between the Bio Bio and Bueno Rivers, as well as on the other side of the Andes in the Argentinian Pampa and Patagonia. Before the arrival of the Spanish, the Mapuche lived as sedentary agro-pastoralists, growing maize, potatoes, peppers, and other domestic plants and raising llamas. Later, they adopted the horse and started growing wheat and barley while continuing to live in small communities based on close family relationships that remain to the present. Between 1550 and 1604 the Mapuche fought the Spanish in what is colloquially termed the “War of Arauco,” in which the Mapuche were victorious and maintained control over their traditional territory. Not until the late 19th century were the Mapuche placed on reservations by the Chilean military, a longer span of cultural independence than any other indigenous group in the Americas.

I argued in my dissertation and subsequent book The Archaeology and Ethnohistory of Araucanian Resilience that how the analysis and presentation of Mapuche-Spanish interactions from 1536 to 1820 and Mapuche-Chilean interactions since 1820 has done a disservice to the archaeological and ethnographic data and has adversely affected the Mapuche today. Primarily, historical research has argued that the modern-day Mapuche exist as a result of Spanish arrival and virtually ignores any pre-1536 information. This has led to the Mapuche losing land rights and standing before the Chilean state, further codified in Chilean law drafted in 1990. My research, and that of other colleagues, demonstrates that the Mapuche have a long and complex history that predates Spanish arrival by centuries, and that despite Spanish efforts the Mapuche were never colonized and managed to maintain strong cultural continuity, limiting the changes to their traditional culture while avoiding the hybridization and syncretism that affected many other Native American societies.

My first presentation on this research was to the Anthropology Department of the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile in Santiago, a growing department with several colleagues who research the modern Mapuche. The presentation had been advertised several weeks prior, with some students coming from as far away as Concepción to listen. About 40 people total came, and the presentation was relatively well-received, though some colleagues took issue with my arguments during the question and answer period, but we are continuing to discuss the points I made.

Two students from the Universidad de Concepción traveled to Santiago to hear my presentation, and afterwards I mentioned I would be in Concepción later in the week. They asked if I would be willing to give a presentation to the Department of Anthropology and Sociology, which fortunately I was able to do. The turnout was also very good, made particularly welcome by a number of Mapuche students in the audience who were intrigued by my presentation. We had a good discussion afterwards, which will hopefully lead to student collaborations in the very near future.

I then travelled to the area of my research, Pucón-Villarrica, to present at the satellite campus of the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile in Villarrica. Fortunately the volcano did not erupt while I was there. I had hoped to be able to meet with several of the Mapuche communities in the area, but the timing did not work out due to some political unrest, but plans are already in the works to meet and present later in the year. In Villarrica, my presentation was attended by students from a nearby High School, the majority of whom are Mapuche. They asked numerous thought-provoking questions (“Wait, you can make a living as an archaeologist?”) and made me rethink some of my arguments related to the development of the Mapuche today.

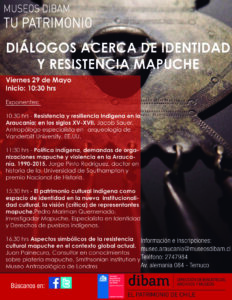

The final presentation came at the Museo Regional de la Araucanía in Temuco, where the materials from Santa Sylvia are currently housed. I started a series of presentations on the topic of “Dialogues about Mapuche Identity and Resistance” as the last in a series of events celebrating Chile’s cultural patrimony. I presented alongside several Chilean luminaries, including National History Award winner Dr. Jorge Pinto Rodriguez, which was somewhat intimidating. It was well-attended, mostly by members of the public. Several audience members liked the archaeological side of things, which they said is rarely presented to the public in this manner, and also that I emphasized the Mapuche perspective over the Spanish which is often how things are presented in their history books and the media.

In all, it was an excellent trip and a marvelous experience and served to highlight the need for interdisciplinary approaches for investigating Mapuche culture. The histories as written often lack the complementary (and critical) anthropological information that can deepen our understanding of the long-term development of cultures worldwide, and how those cultures continue to develop today. Many of my Chilean colleagues were impressed that the Wenner-Gren foundation offers the Engaged Anthropology Grant program, and more so that Wenner-Gren funds the research of investigators living outside the United States. Hopefully there will soon be an increase in the number of applications from Chile! Many thanks to the Wenner-Gren Foundation for generously supporting this research.