Engaged Anthropology Grant: Sara Safransky and “Detroit: A People’s Atlas”

Sara Safransky is an assistant professor of geography in the Department of Human and Organizational Development at Vanderbilt University. In 2011, while a doctoral candidate at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, she received a Dissertation Fieldwork Grant to aid in research on “Breaking Ground: Urban Farming, Property, and the Politics of Abandoned Land in Detroit,” supervised by Dorothy Holland. During her dissertation research, she co-developed an engaged research project called Uniting Detroiters with Linda Campbell, co-director of Building Movement Detroit, and Andrew Newman, assistant professor of anthropology at Wayne State University. In 2014, she was awarded the Engaged Anthropology Grant to return to Detroit to aid in engaged activities on one of the Uniting Detroiters key projects called Detroit: A People’s Atlas. In this blog, Safransky describes how her dissertation research led her to become involved in Uniting Detroiters and the scope of the Atlas project.[1]

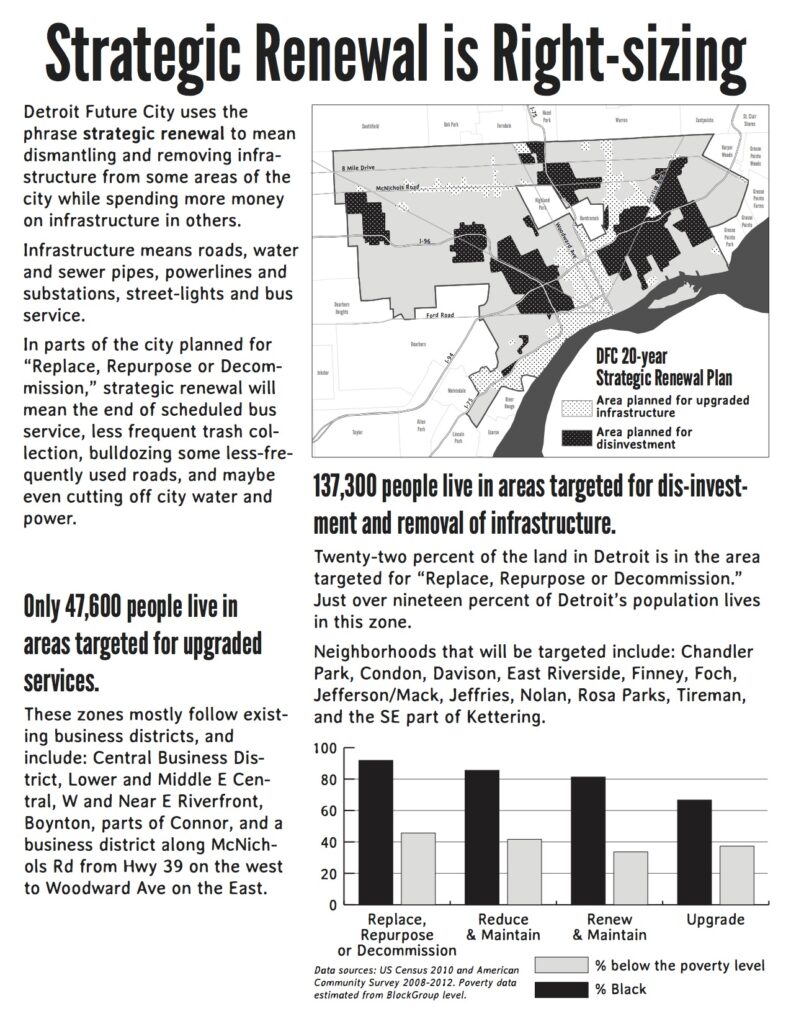

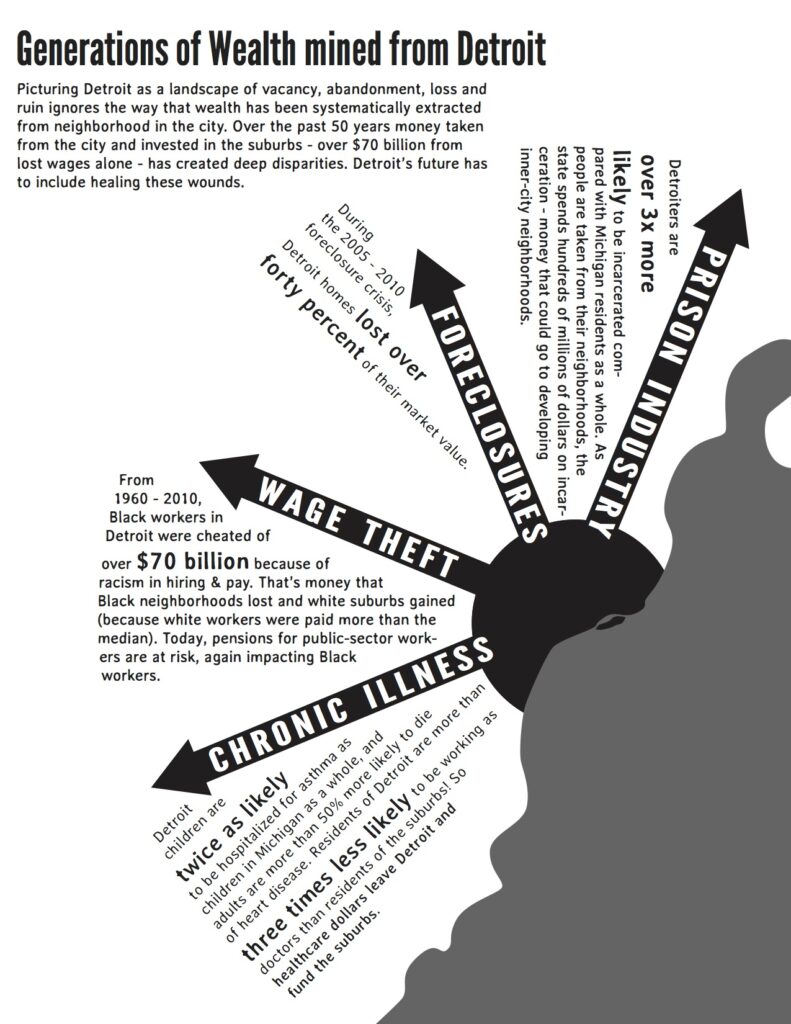

Detroit faces a land crisis that is without parallel in a U.S. city. City officials classify a staggering 100,000 lots – or one-third of Detroit’s landed area – as “vacant” or “abandoned.” In 2010, then Detroit mayor David Bing launched the Detroit Works Project, a contentious planning process that aimed to “right size” the city – or fix the so-called spatial mismatch between surplus land and a reduced population. Arguably the most radical reimagining of a modern city to date, Bing suggested that service delivery go to neighborhoods considered to have market potential. Meanwhile, the areas with less potential for development would be repurposed as urban farms and wilderness zones. The proposal seemed predicated on the incorrect idea that depopulated areas were empty.

One does not have to be in Detroit long to recognize that official and popular media categorizations of land as “vacant” or “abandoned” obscure more than they reveal. First, “vacant” land in Detroit is not vacant in the psychological sense because it is layered with deep feelings of historical loss and racial injustice that haunt the metropolitan region. Second, vacant land is not vacant in practice. Neighborhood residents occupy the land, care for it, and use it. At a community meeting, one woman encapsulated the sentiments of many activists and neighborhood residents when she said: “We don’t call it vacant … we say ‘open space’ … land that is open space is held in the commons, held by the people.”

My research examined these two ways of seeing the city’s so-called abandoned lands – as surplus and commons – and the how urban greening and agrarian projects took different forms in relationship to each. Towards this end, I conducted 17 months of ethnographic fieldwork and collaborative participatory research in Detroit between 2010 and 2012. As a white woman from outside Detroit, I faced questions about what it means to engage in ethical research in a place where many community activists expressed their frustrations with extractive journalism and research.

As I grappled with these questions, I had a fortuitous meeting with Linda Campbell, who directs an organization called Building Movement Detroit. She and her community partners were in the beginning stages of a power analysis of Detroit’s development and social movement landscape. We discussed how my dissertation might be useful for and benefit from such a project. She invited me, and also Andrew Newman, an anthropology professor at Wayne State University to be learning partners, and the three of us worked with other community activists to develop a participatory research project called Uniting Detroiters. Over the past three years, the project has brought together residents, activists, scholars, students, social justice organizations, and neighborhood groups to study and discuss the emerging development agenda in Detroit, its place in broader national and global trends, and local challenges to and opportunities for transformative social change.

In recent years, the global attention directed at Detroit by journalists, filmmakers, artists, and writers has produced an image of the city that is often far removed from the daily lives of residents, and yet is so imposing in its power that all narratives of Detroit must contend with it. This imagined Detroit is marked by several now predictable themes, including the conflation of a very real depopulation process with sensationalized imagery of “post-apocalyptic” emptiness, the erasure of the Motor City’s rich history, and the casting of the city as a blank slate waiting for salvation by heroic entrepreneurs. Now, at precisely the moment the city has reached an important crossroads, these same themes appear to have migrated from the realm of film and journalism into the official maps that plot the city’s course for the future. Indeed, since the inauguration of the controversial Detroit Works Project, mapping has become part of a new, high stakes polemic over the city’s future.

The Uniting Detroiters project has sought to intervene in this development predicament by using research to strengthen the city’s long vibrant grassroots sector and reassert residents’ roles as active citizens in the development process. Toward this end, we are in the process of competing two movement-building tools: a documentary called “A People’s Story of Detroit” and a book called Detroit: A People’s Atlas, the latter of which was supported by the Wenner-Gren Engaged Anthropology Grant.[2]

A community project organized by scholars and activists, but mostly written by and for a public audience, the Atlas starts from the premise that maps are not merely illustrations of reality but better understood as propositions: arguments about the way the world works or should work. We see a clear link between the exclusion of Detroiters’ day-to-day experiences from dominant mappings and narratives of the city and the alienation of residents from the democratic process, and the erosion of their rights. Therefore, the Atlas offers a counter-narrative of Detroit’s redevelopment by remapping the city from below. The maps making up the Atlas do not simply locate things in physical space, but re-situate communities and re-imagine the limits of what a city can be as an urban, ecological, social, and cultural space.

Maps are among the most important conceptual and visual elements of the book, but there is far more to the Atlas than cartography. Detroit: A People’s Atlas includes a wide variety of essays, stories, photography, and poems contributed by over 20 residents from Detroit and Windsor. It also draws on research that we conducted as part of the Uniting Detroiters project, including over 47 interviews and 16 oral histories with individuals involved in social justice organizations and neighborhoods groups and transcripts from a series of workshops on land justice, which approximately 150 residents attended. The aims of these workshops were to share information about the political-economic and territorial reconfigurations underway in the city and discuss progressive land-use alternatives. The Uniting Detroiters project also supported community groups in participatory mapping project, some of which will be published in the Atlas. A ten-member community-based editorial advisory board has helped plan and organize the project.

The core argument that animates the diverse array of community perspectives in the Atlas is that having the power to map is to be empowered to define one’s own political, cultural, and even spiritual space. The thirty maps that make up the Atlas plot not only points in space, but efforts at self-determination, democratic governance, and creativity. The innovative creativity and dynamism of Detroit’s grassroots organizations are globally known among social activists and academics and yet excluded from many narratives about the city as of late. In this respect, Detroit: A People’s Atlas sheds light on an underappreciated aspect of the city’s present that nonetheless has deep roots in its past. It seeks to offer vital perspectives on the city that are absent from “official maps.” Even more importantly, these maps offer a fresh perspective on what cartography and mapping can mean at a universal level; in this respect the book offers not only a new perspective on Detroit, but also represents an important contribution to the field of critical urban studies. We expect a release date of Detroit: A People’s Atlas in 2017.

Abstract

A Wenner-Gren Engaged Anthropology Grant supported Sara Safransky’s involvement in community-based activities associated with Detroit: A People’s Atlas. During Safransky’s dissertation research, she became actively involved in the United Detroiters project, a collaborative effort based on the idea that collective research and reflection are important for creating a more just and equitable city. Detroit: A People’s Atlas is a community-centered writing and mapping project that connects life histories and everyday urban experiences with political-economic reconfigurations in the city (e.g., state takeover, bankruptcy, austerity, rightsizing) and broader structural changes taking place in other cities across the country and globe. The Atlas is designed to take stock of social justice work happening across Detroit and build movement networks in the process. In addition to maps, the Atlas includes critical and personal essays, poetry, photographs, interviews, and oral histories. Through these visions and stories the Atlas counters blank slate narratives about the city often portrayed by the corporate media and many of our politicians. The Atlas is being written for the broadest public with an expected release of 2017.