Engaged Anthropology Grant: Kathleen Rice

While a doctoral student at the University of Toronto, Kathleen Rice received a Dissertation Fieldwork Grant in 2011 to aid research on “Purity, Propriety and Power: Negotiating Lobola and Virginity Testing as Sites of Gendered and Generational Power among Xhosa South Africans,” supervised by Dr. Janice Boddy. In 2015 Dr. Rice received an Engaged Anthropology Grant to aid engaged activities on “In My Youth We Cared About Each Other: An Oral History Film of Xhosa Elders”.

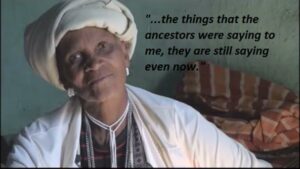

My Engagement Project took the form of a subtitled film composed of a series of oral history interviews with elders from the rural Xhosa community where I carried out fieldwork for my doctoral project. Shortly prior to my doctoral fieldwork, local leaders decided to collect video-recorded oral history interviews with village elders. The impetus for collecting these stories stemmed from an awareness that local elders had lived under Apartheid and through the years of transition, and have watched their children and grand-children grow up in the new South Africa. As elders continued to pass away, community leaders became increasingly concerned that these valuable memory were being lost. Accordingly, video-recorded oral histories were envisioned as a way of preserving the experiences and wisdom of these elders. And according to community leaders, this wisdom is vital for guiding the younger generation, who are widely perceived by their elders as being wayward and in need of guidance.

A few months before I began my doctoral research, community leaders appointed a young local man named Thembela (a pseudonym) with the responsibility of collecting these interviews. With the assistance of a local NGO, the community had secured funding to purchase a video camera, and to bring a documentary filmmaker from Johannesburg to train the young local filmmaker. However, several months into my fieldwork I learned that the project was not moving forward. Speaking with Thembela, I learned that he felt ill-equipped to pose questions of elders in a manner that would elicit the desired form of open-ended reflection. To overcome this obstacle, the NGO director (a non-Xhosa South African who resides in long-term in the area) spoke with community leaders and then approached me to ask if I would be willing to assist Thembela with the project. From the NGO director’s perspective, my skills as an anthropologist might be useful in successfully carrying out the interviews. Furthermore, my dissertation research broadly focused on the gendered and generational politics of social reproduction, and in particular on how local people navigate domestic and intimate relations in a time of economic precarity and rapid social change. Therefore, from the perspective of community leaders my expressed interest in elders’ lives reflected the spirit of the envisioned project. I was pleased to be invited to help, and agreed to assist Tembela in collecting the interviews.

Over the following months Thembela and I worked together to collect ten oral history interviews with elders. The interviews range between twenty and ninety minutes in length, and are all in isiXhosa (the local language). The content of these interviews covers descriptions of daily life in youth and young adulthood, experiences and reflections on the years of transition from Apartheid to non-racial democracy, differences and similarities between their life experiences and those of their contemporary young people, as well as wisdom that that interviewees felt motivated to impart to youth. Most interviews feature rich personal anecdotes.

The project remained unfinished when I left the community in 2012, but at that time Thembela was diligently working on editing the interviews. However, Thembela ended up leaving the community for personal reasons, leaving the project unfinished. Accordingly, my Engagement Project entailed completing the film –now referred to in the village as the Storytelling Project, – and also using the film as a reference point for sharing my dissertation research with the local community. To that end, with Wenner-Gren support I edited the videos to create a short film with English subtitles. For this, I required the assistance of a translator, as elders speak a version of isiXhosa (the Xhosa language) that is rich in metaphor, and is consequently difficult for me to interpret without assistance. Through the South African Translators Institute I was able to connect with two excellent translators: Mr. Jeff Nyoka, and Nombeko at Bohle Language and Translation services. With their assistance, I was able to complete the film.

With the film complete, I returned to the village in March 2016. As the full version of the film is over four hours long, I hosted a showing of segments of the film was in the local library. The showing was open to all interested members of the community, and everyone was informed that the full film would be left in the library. Following the showing, I used content for the film as a reference point for a discussion the findings and implications of my doctoral research.

A copy of the film, as well English and isiXhosa transcripts of the interviews, are accessible in the community library. I intend for them to remain there, and will be available to future researchers, the local community, and members of the South African public. At the time that I am writing this, four of the ten interviewees already passed away, one within the past few weeks. Independent of my own research interests, I hope that these interviews will be of value to the friends and family that these elders have left behind.