Engaged Anthropology Grant: Melanie Martin

Melanie Martin is a Postdoctoral Associate at Yale University. In 2012 while a doctoral student at the University of California, Santa Barbara she received a Dissertation Fieldwork Grant to to aid research on “Maternal Factors Influencing Variation in Infant Feeding Practices in a Natural Fertility Population,” supervised by Dr. Michael Gurven. In 2016 Dr. Martin received an Engaged Anthropology Grant to aid engaged activities on “Targeting Early Life Health Risks Among the Tsimane Through Mixed Educational Outreach Modes”.

I had studied infant care and feeding practices among the Tsimane from 2012-2013. The Tsimane are a hunter-forager population residing in the Bolivian Amazon, with a high burden of infectious disease. Tsimane mothers breastfeed intensively for 2 years or more, but introduce complementary foods relatively early (around 4 months on average). My research examined maternal perceptions of infant needs and other motivations influencing their feeding decisions, as well as variation in infant nutritional status associated with variation in the timing and quality of complementary feeding. Though not the primary focus of my investigation, my research documented local inequalities in prenatal care and vaccine coverage, as well as modifiable behaviors related to child nutrition and antibiotic usage that could be targeted through educational initiatives. With the Wenner-Gren Engaged Anthropology Grant, I returned to Bolivia in July of 2016 to revisit the families that had participated in my study, and present these results to the wider Tsimane community.

I first presented formal reports of my results to three organizations that provide or at times help facilitate health care for the Tsimane: the primary health clinic servicing the Tsimane (Horeb), the Gran Consejo Tsimane (the local governing body of the Tsimane), and the Estacion Biological de Beni (EBB), the bioreserve in which several of my study communities were located. During my field research, the EBB transported physicians to these villages when they otherwise lacked the funds to do so, thus facilitating the only available preventative care for many pregnant women and children—a fact which I highlighted in my report.

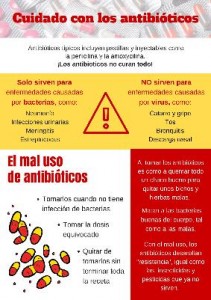

Following these meetings, my assistant Bernabe Nate and I gave a 15 minute radio broadcast discussing my results on Radio Horeb—a mission-operated AM station broadcast in most Tsimane homes. In discussing results of our project, we encouraged families to eat eggs, papaya, butternut squash, and legumes– foods that are rich in vitamin A and other nutrients that support healthy growth, development, and immune function. My research showed that although many Tsimane families cultivate these foods, children infrequently consume them. I had also documented fairly extensive misuse of antibiotics, which can be purchased over-the-counter at local pharmacies and market kiosks. Antiobiotic misuse and rising bacterial resistance are global problems, but the Tsimane have received little to no education on safe antibiotic usage. We used horticulture analogies and existing public health campaigns to explain how bacterial resistance develops, to warn families against administering antibiotics for common cold and flu symptoms, and to encourage them to purchase antibiotics only in a pharmacy after consultation with a doctor or pharmacist (to ensure the antibiotics are not expired and will be administered in the proper dosage). I created two educational posters depicting these messages, which were delivered to the Gran Consejo and the health clinic at Horeb, and presented to study villages in community meetings.

The community visits allowed me to answer additional questions about my research, and visit the many families who participated in my research or otherwise welcomed us into their communities. These visits were the most gratifying part of my trip (and not just because it was prime fishing season, and I was invited to enjoy many massive meals of delicious, fire-roasted fish!). The infants I had worked with were all now 3-5 years old, and many mothers had had other children since then. They were delighted when I showed them pictures of my own daughter, now 3, who I was pregnant with while in the field. Tellingly, many families also asked, somewhat perplexedly, “so you’re not going to do any interviews?”, when I first showed up in their villages, and then smiled warmly when I replied, “jam, sobaqui momo” (“no, I’m just visiting.”).

In truth, though the educational messages were well-received, I can’t say how effective they were. But that is really beside the point, as ultimately this research was as much a collaborative effort with participants as a product of my own design and analysis. The Tsimane I spoke with appeared to understand and appreciate the initiative to share that joint knowledge with them, irrespective of what they ultimately do with it. It is difficult for researchers working in remote locations to make trips without a specific research agenda, and circumstances often move early career anthropologists to work with new populations. This was certainly true in my case, for which reason I remain grateful for the opportunity to reconnect with study participants and interpret meaningful aspects of my research, and their participation in it, for the wider Tsimane community.