Engaged Anthropology Grant: Nidhi Mahajan

While a doctoral student at Cornell University, Nidhi Mahajan received a Dissertation Fieldwork Grant to aid research on “Merchants of Mombasa and the Making of a Shadow Economy,” supervised by Dr. Viranjini Munasinghe. In 2016 Dr. Mahajan received an Engaged Anthropology Grant to aid engaged activities on “Illegality and Maritime Trade in Coastal Kenya: A Public Dialogue on Economic Transformation”.

Fort Jesus is an imposing structure that lies atop a coral ridge with a sweeping view of Mombasa’s harbor – an ideal point from which to watch ships pass in and out of the Swahili port city. This was indeed, one of the purposes of the fort, designed to look like a person laying down, their head to the sea. Built by the Portuguese sometime between 1593 and 1596, to secure their position in this part of East Africa and their ambitions across the Indian Ocean, the building is now a UNESCO World Heritage site. Upon visiting the fort, now a museum, one cannot help but be struck by a mural presumably done by unknown Portuguese mariners from the sixteenth century – hand-drawn images of ships, mythical sea creatures, sailors, and the sea – carefully preserved within the museum’s walls, natural light in the display room playing tricks on one’s imagination, the past casting shadows upon the present. The fort marked the violent entry of the Portuguese into the Indian Ocean. Where once no state claimed authority over the sea, the Portuguese in the fifteenth century (followed by the Dutch and British) wed cannons with trade, and altered the shape of history. Trade that was once carried on freely across the Indian Ocean, came to be regulated by colonial states who ruled with the force of the gun.

My dissertation project examined the contemporary resonances of this long history of tension between Indian Ocean trade networks and the state in East Africa, focusing on the creation of a shadow economy in the Indian Ocean. Examining the entanglements between the sailing vessel or dhow trade and multiple regulatory regimes in the western Indian Ocean, I argue that these trade networks have been pushed into a blurry realm between legal and illegal trade by states as they pose a threat to state sovereignty. When I returned to Kenya in 2016, it was fitting that the Fort Jesus Museum became a space for engagement. While the museum is usually where objects such as ivory, jewelry, and intricately carved furniture from the Swahili coast are carefully displayed in glass cases, the photo exhibition I curated for the museum emphasized a humble object – the mangrove pole.

Mangroves poles from the swamps of the Lamu archipelago in northern Kenya were once harvested and exported out to the Middle East, where they were used for structural timber in homes. Sailors from Oman, Iran, and India would arrive in Lamu with goods like carpets, food stuffs, dates, furniture, and porcelain and carry back cargoes of mangrove poles, animal hides, ivory and even enslaved peoples from these shores. While scholars have written much about these luxury goods, mangrove poles, a key export from the Swahili coast have rarely been examined by scholars. This mangrove pole trade however, structured economic life in Lamu, employing a large number of its residents as cutters, porters, merchants, and transporters. While the mangrove pole export trade came to an end in the 1980s, as the government of Kenya banned the trade citing concerns about environmental conservation, many of those involved in the trade viewed its illegalization as wrapped up in other political economic concerns. Some say that the trade was banned to prevent ivory smuggling, while others believe it was a way for the state government to purposefully impoverish this community that lies at the margins of the Kenyan state. Regardless, the mangrove pole trade is well-remembered in Lamu, even if it remains undocumented.

Mangroves poles from the swamps of the Lamu archipelago in northern Kenya were once harvested and exported out to the Middle East, where they were used for structural timber in homes. Sailors from Oman, Iran, and India would arrive in Lamu with goods like carpets, food stuffs, dates, furniture, and porcelain and carry back cargoes of mangrove poles, animal hides, ivory and even enslaved peoples from these shores. While scholars have written much about these luxury goods, mangrove poles, a key export from the Swahili coast have rarely been examined by scholars. This mangrove pole trade however, structured economic life in Lamu, employing a large number of its residents as cutters, porters, merchants, and transporters. While the mangrove pole export trade came to an end in the 1980s, as the government of Kenya banned the trade citing concerns about environmental conservation, many of those involved in the trade viewed its illegalization as wrapped up in other political economic concerns. Some say that the trade was banned to prevent ivory smuggling, while others believe it was a way for the state government to purposefully impoverish this community that lies at the margins of the Kenyan state. Regardless, the mangrove pole trade is well-remembered in Lamu, even if it remains undocumented.

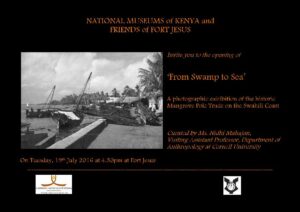

As part of my engagement project, I curated a photo exhibition for the Fort Jesus Museum titled “From Swamp to Sea: The Mangrove Pole trade on the Swahili Coast.” Using photos in the archives of the Museum as well as private collections, the exhibit pointed to the complexities of the trade and its regulation. It opened on 19th July 2016, in Mombasa and will travel to other museums in Lamu and Malindi, on the Kenyan coast. On the day of the opening, I presented a lecture on the trade and its history in an effort to share my research with the community. Residents of Lamu and Mombasa present at the opening expressed their surprise on seeing an exhibit of a quotidian good in a museum, the curator of Fort Jesus even exclaiming, “We must think of history through these everyday objects!” as we discussed the political and economic ramifications of the trade and its ban.

For the rest of the project, I shared the results of my research with both, my interlocutors and the academic community in Kenya. I presented a public lecture “The Contemporary Dhow Trade in the Western Indian Ocean,” to residents of Mombasa at the Friends of Fort Jesus Seminar program. Against the backdrop of the fort, we discussed shifting regulatory regimes in the Indian Ocean, smuggling, and neoliberal economic transformations that threaten communities of seafarers and merchants across the Indian Ocean littoral.

These discussions then shaped a talk at the British Institute in Eastern Africa in Nairobi, Kenya, where I gave a seminar titled “A Sea of Suspicion: The Dhow Trade and Dispossession in the Western Indian Ocean.” Attended by academics based in Nairobi, the talk gave me the opportunity to communicate research findings to specialists of East Africa who don’t work on the Swahili coast, but are nonetheless engaged with broader debates about political economy in the country.

This engaged anthropology grant therefore enabled me to return to Kenya, to build on old connections and forge new ones as I communicated my work in different formats to the academic and non-academic community in Mombasa and Nairobi.