Engaged Anthropology Grant: Amelia R. Hubbard

Amelia Hubbard is Assistant Professor in the department of Sociology & Anthropology at Wright State University. In 2009, while a doctoral student at Ohio State University, she received a Dissertation Fieldwork Grant to aid research on ‘A Re-examination of Biodistance Analysis Using Dental and Genetic Data,’ supervised by Dr. Debra J. Guatelli-Steinberg. She was subsequently awarded the Engaged Anthropology Grant to aid engaged activities on ‘Engaging Prehistory Through Genetic and Dental Variation Among Kenya’s Coastal Communities.’

5 schools, 4 communities, 1 month

Around a week was spent in each of four communities within Kenya’s coastal province: Mombasa, Lamu, Dawida, and Kasigau. The intended goals of the trip were to: 1) reconnect with participant communities from my 2010 dissertation project, 2) connect with the (potential) next generation of Kenyan anthropologists, and 3) share results with academic communities.

In total, 700 individuals were formally contacted during school visits and open houses. Approximately 100 additional individuals were contacted during informal conversations with community members interested in the project.

Goal 1: Connecting with the community

Often, participants are not afforded the opportunity to learn much about the final results of a study, particularly when publications are printed in journals and languages that are inaccessible to local communities.

Non-technical posters (in Swahili and English) were displayed in six easily accessed locations. Paper copies of the text were also handed out to any interested parties so that individuals who could not attend presentations (due to age, illness, cultural restrictions, or busy home lives) still had access to the results.

In the Taita Hils (Kasigau and Dawida), display locations included dispensaries and libraries.

On the coast (Mombasa and Lamu), posters were displayed in cultural centers and open access museums.

In each location, I also arranged a series of barazas (open meetings) where community members could ask questions about the research results. To facilitate higher attendance, local elders coordinating community projects helped identify times when these projects would be taking place and arranged time to talk with community participants. In some villages, elders and project leaders also imparted the importance of understanding Taita (pre)history and supporting future projects in the area.

In a few areas, barazas were not possible and the results were disseminated via more informal conversations among community members and by distributing handouts. Individual home visits were not conducted, to protect the identities of past participants and to avoid giving the appearance that I had “favorites.”

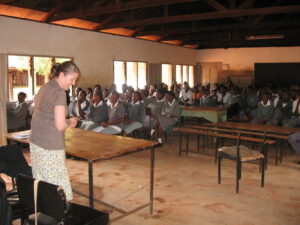

Goal 2: Inspiring the next generation

Initially, this component of the project was touch and go. Upon landing in Kenya, I was informed that all high school teachers were on strike and schools had been closed indefinitely. Fortunately, some public boarding schools still had students. Additionally, with the national exams quickly approaching, many of the Form 4 students (HS Seniors) were studying on their own rather than returning home where family and work obligations would hinder their ability to prepare.

In total, I was able to visit five schools: Moi Secondary (Kasigau), Lamu Girls School (Lamu), Dr. Aggrey Boys School (Dawida), Mwangeka Girls School (Dawida), and Kenyatta Secondary (Taita). The reception was warm and students were very inquisitive. Questions ranged from, “what are the major benefits of studying anthropology in college?” to “what were the challenges of conducting research?”

Through additional funding from Wright State University, I was also able to create informational posters (with help from my research students) about the subfields of and careers in anthropology to give to schools and educational institutions.

As part of the funding, two of my undergraduate research students (who have been working on the study collection from the 2010 project) traveled to Kenya to assist with the trip. They proved vital in documenting the project and facilitated additional engagement with communities by allowing local students to interact with “real” American students. Through this experience they also gained their own rewards: both are now certain that public health, medical anthropology, and international development are areas they will pursue in graduate school.

Though I anticipated my students’ popularity among local high schoolers, I could not have guessed at the impact of their speeches, especially among female students.

Chris, a mother of two and full time student, told students about her choice to return to school after having a family, despite the financial and emotional struggles of balancing both responsibilities. Though most female students found it unusual for a woman to return to school after having had children, they also vocalized how her story was inspiring and gave hope that they could be both mothers and scientists someday.

Kaitlin, a 20-year old considering medical school, impressed students (many of whom themselves are the same age) with her commitment and focus to both anthropology and medicine. She articulated why her training in anthropology would make her a good doctor and explained why studying language, culture, and history are relevant to students interested in science.

The added bonus of their interactions with students furthered my intended goal of inspiring the next generation of Kenyan anthropologists and was an important contribution to the overall EA project.

Goal 3: Academic presentations

As anyone who does research abroad can attest, there are many challenges in coordinating a research program from the other side of the world. In the US we’d say “the best laid plans…” and in Kenya we’d say “haraka, haraka haina baraka” (hurry, hurry has no blessings) or “hamna shida, tutashinda kesho” (no worries, there’s always tomorrow).

In preparation for my EA project, I diligently contacted colleagues to arrange workshops and talks at various institutions around Kenya. Unfortunately, due to illness, scheduling conflicts, and other roadblocks I was ultimately not able to fully complete this component of the project.

I was still able to meet a few anthropology undergraduates from Pwani University and University of Nairobi to talk about research on the coast. One student I spoke with is currently a Kiswahili and History instructor at Kenyatta Secondary School in the Taita Hills and initiated a meeting with students to talk about my research and careers in anthropology.

Final thoughts and lessons learned

Despite a few setbacks, my EA project was a success and I see that the impacts are varied and ongoing.

First, there is the impact on the community. Many people articulated how pleased they were to see a researcher return with study results. A common phrase was, “Everyone says they’ll come back, but they don’t.” Through e-mail, Facebook, and calls to my research assistants it appears that people are still talking about the project (i.e., spreading the word) and visiting the posters.

Second, there is the impact on youth. It has only been a week and a half since we left but I have followed up with teachers via e-mail and post to reiterate my commitment to providing informational resources about studying anthropology at the collegiate level. Informal discussions with principals and administrators about internships and job shadowing also have the potential to create networks between future research projects and students interested in anthropology.

Third, this opportunity to reconnect with participants, friends, and colleagues has strengthened relationships between myself and these communities, allowing for greater success in future research endeavors.

Thank you Wenner-Gren for this wonderful opportunity. And thank you to the people of coastal Kenya for your continued hospitality.