Engaged Anthropology Grant: Elsa Fan

Elsa Fan is an Assistant Professor of Anthropology and Human Rights at Webster University. In 2010 while a doctoral student at the University of California, Irvine she received a Dissertation Fieldwork Grant to aid research on “Opportunistic Infections: The Governance of HIV/AIDS in China,” supervised by Dr. Tom Boellstorff. In 2015 she received an Engaged Anthropology Grant to aid engaged activities on “People, Profit and Prevention: Scaling-up HIV Testing in China”.

How has the scaling-up of HIV testing among men who have sex with men (MSM) in China impacted, if at all, the work of community-based organizations (CBOs) engaged in HIV prevention? What progress has been made towards reducing new infections through this intervention? These are some of the questions I sought to explore when I returned to Beijing, China in the summer of 2015 to hold a workshop on July 11 to discuss the impacts of expanding HIV testing as an intervention. With the support of the Engaged Anthropology Grant, I planned to bring together multiple stakeholders involved with such programs to assess the effects of these interventions, potential challenges, and long-term strategies for the future.

This grant builds on my fieldwork from 2010–2011 where I traced the emergence the HIV testing as a model par excellence for reducing new infections, and the targeting of the MSM population in which to scale-up this intervention. The turn to this approach stemmed in part from the increasing rates of HIV infection among MSM. Since 2007, sexual contact had become the leading route of HIV transmission in China; in particular, there has been a significant rise through homosexual contact. For instance, homosexual contact accounted 25.8 percent of new infections in 2014 (compared to 3.4 percent in 2007), and HIV prevalence rates among MSM increased to 7.7 percent in 2014 from (National Health and Family Planning Commission 2015). In response, public health institutions and international donors turned to promoting HIV testing in this population in order to ensure more men are aware of their serostatus, thus enabling them to start antiretroviral treatment as needed and engage in safer sexual practices to reduce transmission. To scale-up this intervention, there were two main strategies adopted: (1) to support CBOs to extend testing services, either for free or for a nominal fee; and (2) to contract CBOs to conduct testing among MSM by the Chinese Center for Disease Control (CDC), a practice called goumai fuwu.

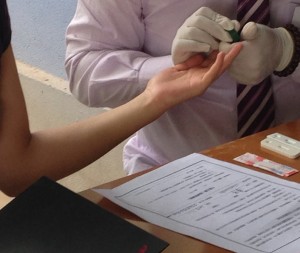

This topic of testing became the fodder for an intense debate during dinner the night before the workshop. I sat with a number of participants from CBOs who had been and continue to be involved with offering testing services to MSM: most for a nominal fee, and almost all for the CDC. One participant complained, “Testing, all I hear these days is testing,” commenting that as a gay man, he was sick of hearing about HIV/AIDS all the time. The others at the table agreed, noting that the main message being conveyed to their community was jiance jiushi ganyu, or testing is intervention; but what about counseling, one person posited. This critique carried over into the workshop the following day, as participants discussed the benefits and challenges to this intervention. The day started out with a demonstration of testing services offered by CBOs; audience members volunteered to get tested, and the organizations carried out pre-test consultations and post-test counseling, and administered a rapid HIV test.

This demonstration set the stage for a provocative workshop. Many participants extolled the positive effects of this initiative, noting that for many men, it has become a good habit, or hao xiguan, a practice that has become a part of their everyday lives. Others, however, critiqued the way in which testing had dominated their lives; “as a gay man,” one participant noted, “I’m sick of being told I need to get tested.” On the other hand, discussions turned to the need for testing, and questioned whether it was something men wanted, or the CDC wanted, as a result of the outsourcing of these services to CBOs. One critical issue that came up was how the focus on testing had excluded other needs in the community, such as addressing the emergence of crystal meth. One of the speakers outlined the increasing use of this drug in the community, and the risk for HIV transmission as a result. Especially provocative was listening to one man who shared his personal story of engaging in unsafe sex while on crystal meth, which led to his HIV infection. It was such stories that led one participant to ask, as he recounted the number of clients that had been repeatedly tested only to still become infected, that “perhaps it is that in the context of testing, we never considered the problem of how men became infected?” This theme was reiterated by other participants from CBOs, who questioned whether testing had become a means or an end; that is, were we testing men for the purposes of HIV prevention, or simply as an outcome to count tests? In other words, as some participants noted, had testing become an intervention in and of itself, to the exclusion of other possibilities? Ultimately, the workshop ended on one critical question: Do we still do HIV testing?

The responses varied; for some CBOs, there was still a demand for it from men in their community. For others, it has become a part of their institutional sustainability, as articulated by one speaker who shared their success in charging for their testing services; men choose to pay for their testing, rather than go to the CDC for free. While no conclusion was reached, the workshop helped to articulate some of the unintended consequences emerging from this intervention, and highlighted important issues that risk being marginalized. It allowed stakeholders to question the purpose of testing, and whether it was being scaled-up for the good of the community, or for the government. In creating a space for such discussions, the workshop brought issues to the fore that enabled those involved with shaping the HIV/AIDS landscape to be aware of the limitations of such interventions.