Roosbelinda Cardenas and ‘Articulations of Blackness: Reconstructing Ethnic Politics in the Midst of Violence’

Roosbelinda Cardenas is Visiting Assistant Professor of Latin American Studies at Hampshire College. She received a Dissertation Fieldwork Grant to aid research on ‘Remaking the Black Pacific: Place, Race, and Afro-Colombian Territoriality,’ supervised by Dr. Mark David Anderson, and in 2013 received the Engaged Anthropology Grant to return to her fieldsite and share her research with the community that hosted her.

Returning to the field is like jumping on a moving train. After doing my best to clumsily get up to speed, I quickly tried to find a reliable reference point to orient myself. With the privileges of hindsight and perspective gone, the pace of events was both confusing and exhilarating. Nonetheless I managed to resist the allure of fresh ethnographic data. Instead of scribbling field notes incessantly and searching for my voice recorder at the first sign of an engaging conversation, I focused on being in the moment. I called old friends and asked them to meet me simply to catch up. Then, after a week of updating contact information and tracking people down, I began the work of planning my engagement activities in earnest.

I had proposed to hold workshops in the three communities where I conducted dissertation research from 2008 to 2010. These communities were: 1. the rural inhabitants of a legally recognized “comunidad negra” that holds a collective land title in the Southern Pacific; the black residents of an urban shantytown in Bogotá where a large concentration of internally displaced people (IDPs) reside; and a group of leading black activists from two organizations that work for the defense of Afro-Colombians’ ethnic rights to territory. My purpose was to share with them a handful of insights that I had gathered throughout my dissertation work and which I thought would be most useful in furthering their strategies to remap racial and territorial politics in Colombia.

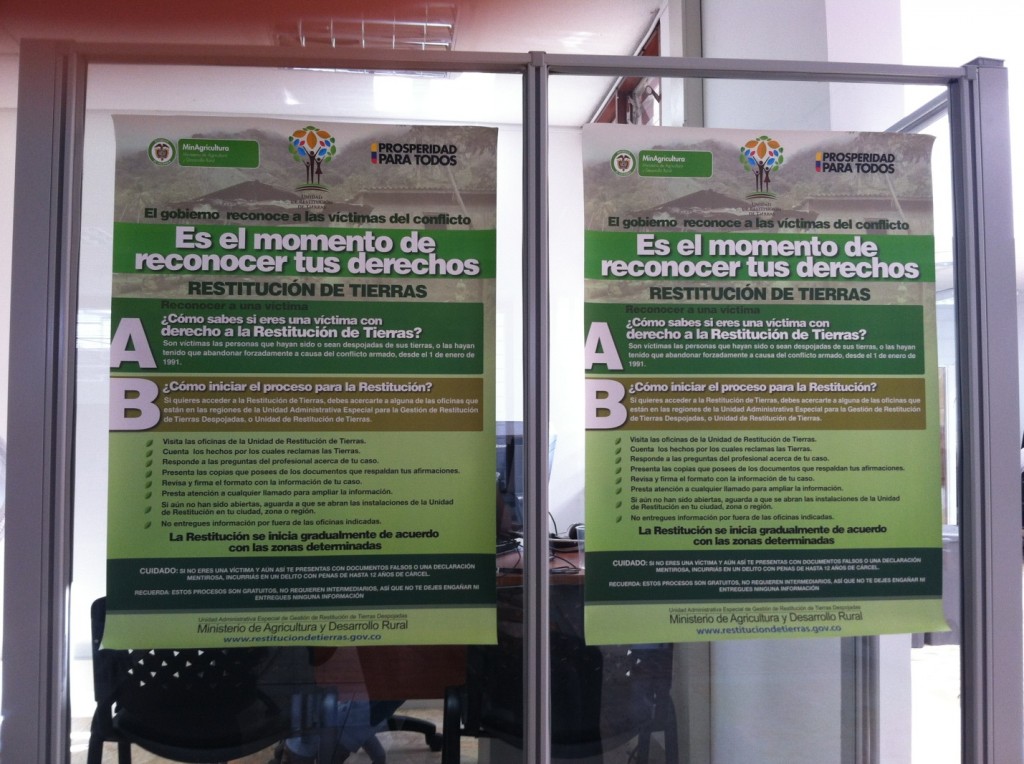

In the rural black community–the Community Council of the Lower Mira River–the timing was particularly auspicious. The Colombian government was in the process of implementing a sweeping land restitution law to return millions of hectares that had been unlawfully taken from their rightful owners in the midst of the armed conflict. Although a number of land restitution cases were already under way, the Bajo Mira’s was the first ethnic-specific case that had been presented to the courts and all eyes were on them. I met with the team of young government representatives who were busy gathering evidence in the field. In addition to meeting with them to share my insights and written work, I agreed to produce a short report that would be included with the dossier that they were preparing for the courts.

I also met with members of the Community Council board to hold the workshop that I had originally planned. Although they humored me by sitting patiently through my presentation and activities, it was clear that their attention was elsewhere. My presentation was focused on an analysis of what I called “green multiculturalism,” or the coupling of multicultural recognition and green capitalism. I had intended to lead a conversation that would both identify and push the limits of “environmentalism” as the most viable political strategy to protect their territorial rights. I still think it is an important conversation, but the timing was not the right one. After decades of being held hostage in their own lands by the criminal advance of the drug trade and other capitalist ventures of global scale, the land restitution process held promise as a tool to protect their territories. If the government asked them to embody the 21st Century version of the noble savage before deeming them worthy of territorial protection, they were ready to comply. This did not mean that they were unaware of the deal they were striking or vigilant of the ways in which it might compromise their political vision, but simply that they were taking advantage of an expedient strategy that held newfound promise to change a situation that was no longer bearable.

In Cazucá, the shantytown of IDPs on the outskirts of Bogotá where I have worked for nearly ten years, spirits were high. I did not prepare a presentation for the group of grassroots activists that I met with there. Instead of starting the conversation with my own insights, I facilitated a workshop that was based on their own experiences of being black and displaced. Ten people with a range of experiences as IDP activists attended. Some were recent arrivals and others were old timers who had literally paved the neighborhood roads with their own hands; there were young mothers and older men; and they hailed from every corner of “black Colombia’s” geography. For the people of Cazucá, the timing of the workshop was very different than for the members of the Lower Mira River’s black community. I had the distinct sense that they finally felt “settled” both literally and figuratively. They had bought homes and started businesses and were no longer on the move. This meant that they were much more receptive to a critical analysis of their political strategies. With the hindsight from their grassroots activism, they were eager to start thinking about how to move forward.

In Cazucá, the shantytown of IDPs on the outskirts of Bogotá where I have worked for nearly ten years, spirits were high. I did not prepare a presentation for the group of grassroots activists that I met with there. Instead of starting the conversation with my own insights, I facilitated a workshop that was based on their own experiences of being black and displaced. Ten people with a range of experiences as IDP activists attended. Some were recent arrivals and others were old timers who had literally paved the neighborhood roads with their own hands; there were young mothers and older men; and they hailed from every corner of “black Colombia’s” geography. For the people of Cazucá, the timing of the workshop was very different than for the members of the Lower Mira River’s black community. I had the distinct sense that they finally felt “settled” both literally and figuratively. They had bought homes and started businesses and were no longer on the move. This meant that they were much more receptive to a critical analysis of their political strategies. With the hindsight from their grassroots activism, they were eager to start thinking about how to move forward.

The last workshop–with national-level black activists from two major organizations–was the most difficult one. Unsurprisingly, it was nearly impossible to get all of them in the same room at the same time. Added to this, were the political differences between the two organizations and the internal turmoil that they were each experiencing. After much insistence, I finally managed to schedule two separate sessions with the most experienced members of each organization. I was particularly nervous preparing for these two sessions. What new insight could I, a foreign white researcher, contribute to a struggle that they knew all too well? But despite my anxiety, when I finished delivering my presentation, I felt satisfied. On the one hand, it felt like the culmination of a very long process to which I had committed much of my adult life. On the other hand, their reactions, which were incisive and receptive, confirmed that critical analysis is an essential part of politics. Our debates were heated, our memories were rich, and I believe that in the end, our analysis was fruitful. It was not often that these activists–my friends–took time out from their busy schedules to reflect upon the work that they did. They were proud of themselves, and they felt inspired to move forward. We talked about risks and obstacles, but also silently celebrated the victories both small and large. On the way home, “Maria Elena” a central character in my dissertation said to me “it’s very nice, to have your life’s work laid out in front of you like that.”

The last workshop–with national-level black activists from two major organizations–was the most difficult one. Unsurprisingly, it was nearly impossible to get all of them in the same room at the same time. Added to this, were the political differences between the two organizations and the internal turmoil that they were each experiencing. After much insistence, I finally managed to schedule two separate sessions with the most experienced members of each organization. I was particularly nervous preparing for these two sessions. What new insight could I, a foreign white researcher, contribute to a struggle that they knew all too well? But despite my anxiety, when I finished delivering my presentation, I felt satisfied. On the one hand, it felt like the culmination of a very long process to which I had committed much of my adult life. On the other hand, their reactions, which were incisive and receptive, confirmed that critical analysis is an essential part of politics. Our debates were heated, our memories were rich, and I believe that in the end, our analysis was fruitful. It was not often that these activists–my friends–took time out from their busy schedules to reflect upon the work that they did. They were proud of themselves, and they felt inspired to move forward. We talked about risks and obstacles, but also silently celebrated the victories both small and large. On the way home, “Maria Elena” a central character in my dissertation said to me “it’s very nice, to have your life’s work laid out in front of you like that.”