Engaged Anthropology Grant: Carwil Bjork-James

Carwil Bjork-James is an Assistant Professor in Anthropology at Vanderbilt University. In 2010 he received a Dissertation Fieldwork Grant to aid research on “Claiming Space, Redefining Politics: Urban Protest and Grassroots Power in Bolivia,” supervised by Dr. Marc Edelman. In 2015 Dr. Bjork-James received an Engaged Anthropology Grant to aid engaged activities on “Public Space, Self-Organization, and Indigenous Values in Bolivia’s Urban Movements”.

My engagement project, centered around an early November trip to Bolivia, brought my research back to the community where I did most of my fieldwork, Cochabamba, Bolivia. My recent work centers on urban social movements in Cochabamba, Bolivia, which became internationally famous for the Water War, a 1999–2000 campaign against the privatization of the public water system that inspired the Goya Award-winning film También La Lluvia. In the years that followed, mass mobilizations taking over central urban spaces were a vital part of nationwide political upheaval, leading to the resignation of two presidents and dramatic political transformations. My dissertation research, conducted in 2010 and 2011 with the support of Wenner-Gren and the National Science Foundation, investigated space-claiming urban protests using oral history interviews, collecting documents, and experiencing the daily realities of protest and political organizing. My research integrates an experiential understanding of mass protest with an analysis of how both racialized and governmental power function in and through public space. By focusing on social life as experienced through the human body, the meanings attached to place, and social movement practices, I explain how race and power are lived and changed through protest.

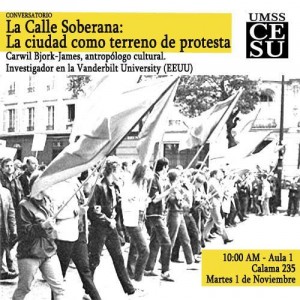

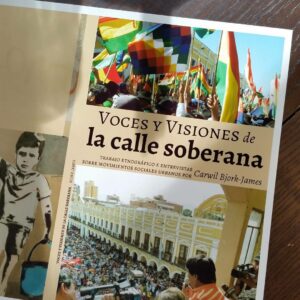

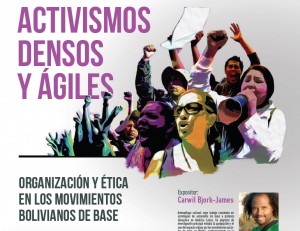

My engagement project involved four components: a 38-page booklet Voces y Visiones de La Calle Soberana (“Voices and Visions of the Sovereign Street”), an academic presentation, a community dialogue with activists and academics, and a collection of twenty photos exhibited alongside the community dialogue. The Spanish-language booklet compiles brief ethnographic descriptions and segments of oral history interviews to document how space-claiming protests (especially road blockades) wield power by interrupting economic life, how urban and rural organizations organize internally, and the role of indigenous values in urban organizations. The booklet is illustrated with photographs and was professionally printed. I distributed 100 copies of the booklet in Cochabamba and had conversations with local contacts about producing and publishing an expanded version.

The Engaged Anthropology Grant offered me the opportunity to share my reflections and research conclusions with activists and academics, two groups that are already very much in dialogue. In contemporary Bolivia, the politics of indigeneity, local autonomy, and community self-organization are well articulated and politically influential. The Documentation and Information Center of Bolivia (CEDIB) and the Centro de Estudios Superiores Universitarios (CESU) of the public Higher University of San Simón, which hosted my two events, are two institutions that reflect a local tradition of engaged research and political commitment.

I organized a research presentation at CESU presenting my findings on protest and public space and a community dialogue (or Conversatorio) at CEDIB discussing forms of self-organization among social movements. The presentation, entitled “The City as Terrain of Protest,” was attended by 20 to 25 students and academics. My research shows that the political import of mass protests in Bolivia arises from their interruption of commercially important flows and appropriation of meaning-laden spaces. These protests put forward a new model for governance of their country by inverting the historic exclusion of the indigenous majority and enacting collaborative forms of democracy in the streets.

The community dialogue brought together over 35 community activists, students, academics, and politically involved expatriates to discuss a series of ideas that I presented about the way that Bolivian movements organize. I argued that Bolivian grassroots organizations have two distinct organizational cultures, each with their own internal ethics. Some grassroots organizations are “dense”—including labor unions and neighborhood associations. These groups are bound together by a formal organizational structure and a countervailing ethic that subordinates leaders to the grassroots bases from which they emerge. Others are “nimble,” involving individuals who join voluntarily without a joint decision by the communities where they live or work, and achieve their political effects by networking. While some of these differences and tensions were familiar to participants, I was able to use ethnographic examples to inspire activists to reflect on their own practice. In conversation, we came to a shared acknowledgement of the interdependence of these often-counterposed approaches to political action.

Photography has been an important part of my fieldwork, and I returned from my research in Cochabamba with over seven thousand still images of protests, public events, public spaces, and daily life in Bolivia. This task of re-presenting the process of protest to a Bolivian audience pushed me to make use of these photographs in a new way to illustrate the process of protest as well as to elicit the emotions associated with its most exuberant or affecting moments. The twenty poster-sized images that were hung at CEDIB during and after my presentation and the ten images that are part of the Voces y Visiones booklet range show mass mobilization as simultaneously a personal and collective activity and illustrate how protesters make the city their own.

During my visit, several of my former interviewees approached me to express appreciation for making the effort to return the knowledge I gained from my fieldwork to Bolivia. While Cochabamba has attracted a fair number of social scientists from the global North, they observed, the relationship has usually been one way. For my part, engaging with on-the-ground researchers at CEDIB and getting feedback from Bolivian academics was invaluable. I’ve long been aware of the rich academic production within the country about Bolivian social movements, but this fall gave me some of my first opportunities to talk productively about my work with them. It also served to cement several relationships that will be crucial for future ethnographic work, and for dissemination of my forthcoming book in the country whose political life it describes.