Engaged Anthropology Grant: Doc Billingsley

Doc Billingsley is a member of the faculty in the Department of Modern Languages, Anthropology, and Geography at Southeast Missouri State University. In 2010, while a doctoral candidate at Washington University in St. Louis, he received a Dissertation Fieldwork Grant to aid research on “Networks of Maya Knowledge Production: An Ethnography of Memory in Practice,” supervised by Dr. Bret Gustafson. In 2015, he was awarded an Engaged Anthropology Grant, which allowed him to return to several of the key communities who participated in his research in Guatemala, sharing the results of his work in a bilingual Spanish-K’iche’ report.

In the five years since I completed my dissertation research, Guatemalan civil society has experienced a number of watershed events: from the short-lived conviction of former President Ríos Montt for genocide, to the election and eventual imprisonment of President Perez Molina after tens of thousands of citizens took up the call for an end to impunity. As I’ve observed these events unfolding and discussed their significance with my Guatemalan friends, I’ve been continually reminded that the questions I set out to study five years ago remain important for understanding the context of these democratic transformations: What is historical memory? How are memory activists expanding the Guatemalan national narrative to include more perspectives—including the experiences of Maya communities who have suffered the greatest burdens of state-inflicted violence? And what are the wider social and political consequences of this democratization of knowledge production?

Thanks to the support of the Wenner-Gren Foundation and a Fulbright-Hays award, I was able to live in Guatemala during 2010-2011, working alongside the members of several influential Maya intellectual organizations that play a role in linguistic and cultural activism. I also became familiar with the groups of activists—primarily young, urban, and Ladino—who draw on historical memory as an organizing theme and objective in their diverse public events, from marches and graffiti campaigns to film festivals and teach-ins. My research gradually shifted to examine the relationship between the projects of these two public spheres—Maya intellectuals and memory activists—and the broader question of how knowledge production can serve to create, shape, and unite publics. I adopted an interviewing method for collecting historical memories from my participants. As I coded and compared narratives from participants of different linguistic communities, age groups, and educational and class backgrounds, I was struck by how much of their knowledge about the past shared common features, patterns, and metanarrative characteristics—a common “gist” to the story of their nation’s past. I also noted that the vision of history presented by my friends and participants differs greatly from the perspectives enshrined in Guatemala’s museums, monuments, and textbooks. I began to imagine the possibilities for returning my findings to the communities who originally shared their experiences, showing them how much they have in common with each other and how their shared perspective may offer an alternative to the stale, racist, status quo version of Guatemalan history.

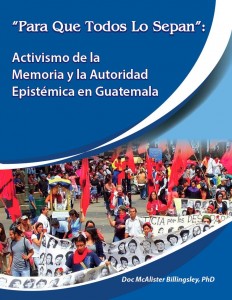

With the support of an Engaged Anthropology Grant from the Wenner-Gren Foundation, I returned to Guatemala in June and July of 2016 to begin this new, collaborative phase in my research. The primary objective I set out in imagining this project was to share some of my ideas about the common features of Maya historical memory, combined with excerpts of the original interviews and some discussion of the theories and methods that informed my work. My preferred means of communicating this information was to prepare a multi-lingual written report, which could be shared and discussed following the model of a book presentation. Based on my earlier work with Editorial Cholsamaj, I knew that published materials featuring Mayan languages or incorporating indigenous forms of knowledge are regarded as symbolically charged indicators of the rising epistemic authority of indigenous communities. That is, regardless of the specific contents of a given book or whether the possessor has even “consumed” the literature, the very existence of the object is recognized as a sign of a revolutionary shift in access to education, citizenship, and human rights. The public debut of printed materials also provides valuable opportunities for members of the public to participate in lively intellectual discussions about topics of interest. These events typically devote at least half of the allotted time to allow questions from the audience—a stark departure from the paltry few minutes typically reserved after a similar talk in the U.S academy. The support provided by the Engaged Anthropology Grant, combined with the editorial assistance and goodwill of my friends at Editorial Cholsamaj, led to the just-in-time production of a visually appealing, short report containing a few key ideas from my dissertation, translated into Spanish and K’iche’. In addition to providing the impetus for gathering in workshops, these printed reports allowed me to leave behind a small yet tangible reminder of each community’s participation in the research and discussion.

Surprises, as Expected

In the course of preparing and carrying out this engagement project, I experienced several interruptions, chance encounters, and logistical challenges. I came to think of these hiccups as “expected surprises”—I knew there would be difficulties as well as serendipitous discoveries, based on past experiences and the wise council of predecessors—Micha Rahder’s post on this very blog a year ago was especially enlightening. Consequently, I tried whenever possible to allow for flexibility in planning, expecting surprises to come along and change my plans—sometimes for the better. Indeed, it felt like every scheduled event was tentative, sometimes right up until its conclusion.

Some of the surprises were known to me in advance, but their full impact was only registered once I was in situ and chatting face-to-face with old friends. Most significant for the project was the news that all of my colleagues in one organization had been dismissed by the newly-elected president of that organization—a move that is fairly typical in state politics, but a new feature in organizations associated with the Maya movements. The economic hardships caused by their sudden lack of employment was an unwelcome sight; the lingering tension between them and the new representatives of their organization was also a complication for my plans. Fortunately, I was able to draw on another NGO in the community to serve as the host for the local workshop—a decision which led to a more diverse audience, in the end.

Other surprises crept up at the last moment, including such happy occasions as one of my friends—and the principal organizer of one of the workshops—going into labor on the same morning we were scheduled to meet. Nonetheless, her fellow teachers showed up in force and participated in the largest and most interactive of the workshops, in the K’iche’ town of Cantel.

Some surprises were the result of technical issues common to our digital age. One of the four workshops was ultimately postponed until next summer, due to simple miscommunication involving email. The preparation of the report was delayed at several points by missing drafts and spotty data coverage, and the task of coordinating translations from multiple assistants required more face-to-face communication—and cross-country bus travel—than I had anticipated. In the end, the three workshops were conducted in a three-day blitz near the end of my trip—not the most restful approach, but nonetheless a satisfyingly climactic and productive end to the trip.

Articulating historical memory: “Power,” “patterns,” and “databases”

One of my goals in this project was to extend discussions of anthropological topics—especially collective or historical memory—to broader audiences, and to evaluate and improve my understanding of the local interpretations of his concept. I was pleasantly reassured that memoria histórica remains a peculiarly salient and widespread topic of interest in Guatemala. The discussions that followed my presentation at each workshop were enormously valuable for me as a researcher, and many participants told me afterward that they appreciated the opportunity to gather and discuss these topics from a thoughtful perspective.

There were three comments in particular that immediately grabbed my attention, each offering a definition of historical memory and its relevance to current events. For one participant, the community of Cantel has a unique relationship with history, in that Cantelenses have on multiple occasions fought back against the status quo or dictates from the state; they have the power to respond as a people, and “Historical memory gives us this power.” Another noted that the contents of Guatemala’s past, as experienced by indigenous communities, are shaped by “patterns of violence and racism” that continue up to today. Another commented on the utility of my project itself, referring to the printed report and our gathering to discuss the topic as a process of transforming historical memory into a “database,” “when it’s shared like now, and written down.”

The Engaged Anthropology Grant allowed me to experiment with new methods of research that are more accessible and collaborative, and ultimately more meaningful for everyone involved. I view this past summer’s project as the pilot for a new, more engaged methodology going forward—I’ve already begun making plans for additional workshops next summer. And with the benefit of first-hand experience, I hope to be better prepared for any more expected surprises that come my way.